Blackstone and BlackRock are starting to cross over into each other’s bread and butter

Larry Fink and Steve Schwarzman were partners before a bitter split early in their careers. Now their dominant firms, BlackRock and Blackstone are getting into each other's business.

Larry Fink and Steve Schwarzman were partners before a bitter split early in their careers. Now their dominant firms, BlackRock and Blackstone are getting into each other's business.

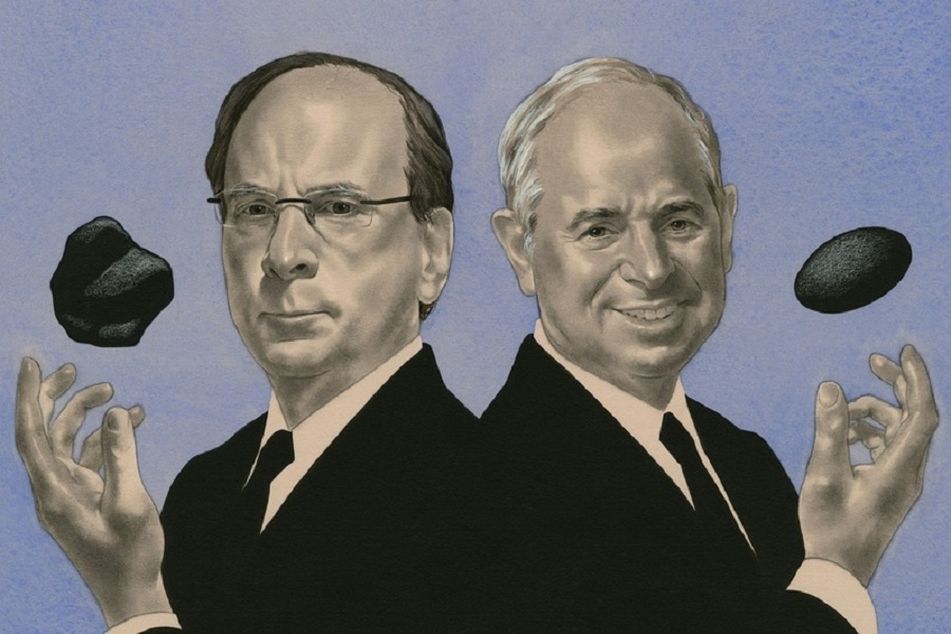

Steve Schwarzman and Larry Fink, once partners, now vie for Wall Street dominance atop their wildly successful firms.

To understand how Steve Schwarzman and Larry Fink, one-time partners who had an ugly breakup two decades ago, today compete for attention among the most powerful people in business and finance, consider the events of a few days in mid-April.

Mr. Schwarzman’s Blackstone Group, the world’s largest alternative asset manager, announced on April 10 that it would pay $14 billion for a portfolio of properties General Electric wanted to shed. The largest real estate transaction since the financial crisis, this deal not only cemented Blackstone’s standing as the biggest landlord on the planet. It also underscored how Blackstone’s financial clout and real estate savvy made it the buyer someone like GE’s Jeffrey Immelt would turn to in the midst of a restructuring.

Mr. Fink and BlackRock, which has become the largest traditional money management firm since being shed by Blackstone, were the ones in the news on April 14. In a letter to the heads of every company in the S&P 500, Mr. Fink, 62, warned about the growing influence of activist shareholders and the dangers of short-term thinking. His missive, written in the plain, direct language he’s known for, showed how Fink is a leader among global investors — and a tough man to ignore, given his firm’s $4.8 trillion.

Such days aren’t even extraordinary for these guys.

ASSET MANAGEMENT BEHEMOTHS

Blackstone’s private equity arm owns companies that employ some 600,000 people, giving Mr. Schwarzman, 68, a unique window on the economy. One of the 10 richest Americans in the financial industry and a generous Republican donor, Mr. Schwarzman has been called on to advise presidents and congressional leaders.

Mr. Fink, as overseer of retirement funds for teachers, cops, firefighters and millions of retail investors, casts himself as a voice for savers. A Democrat, he has provided counsel to central bankers and heads of state, and is quick to mention these interactions in conversation. Fink’s name was raised when President Barack Obama was looking for a new U.S. Treasury Secretary in 2012.

James B. Lee Jr., in an interview for this story a few weeks before his sudden death on June 17, said his friends Mr. Schwarzman and Mr. Fink both enjoy remarkable influence due to the success of their companies.

“They have fabulous platforms that create a megaphone for them,” said Mr. Lee, who was vice chairman and a legendary dealmaker at JPMorgan Chase. “That gives them considerable voice within both business and political circles.”

Their megaphones are only getting louder as Blackstone and BlackRock gather more assets, expand into new activities and extend the leads they enjoy over their closest competitors. And now, they’re getting into each other’s business.

Blackstone and BlackRock say they aren’t direct rivals. Mr. Schwarzman, when the topic is raised, says his company and Mr. Fink’s overlap very little, though he also says change is constant in his world.

“It’s a business without patents,” he says. “Innovation is a requirement.”

Blackstone President Tony James says it’s always possible that BlackRock could buy one of his direct competitors in the private equity field, though he knows of no such plans.

Mr. Fink, through a spokesman, declined to be interviewed for this article after being told it was for a rivalry-themed issue of Bloomberg Markets. BlackRock co-founder Ralph Schlosstein, who left in 2007 and now runs the investment bank Evercore Partners, says Mr. Fink worries not at all about Blackstone: “They are in completely different businesses.”

On the surface, this is true. In the decades since the breakup, BlackRock has grown by managing money for pension funds and retail investors. It runs the world’s largest collection of exchange-traded funds — iShares. It invests primarily in stocks and bonds and is almost always long-only.

Blackstone, on the other hand, has become a $300 billion giant in the world of alternative assets — private equity, hedge funds and real estate — serving institutional clients almost exclusively.

Each firm has become so dominant that it essentially defines the category it inhabits. BlackRock doubled its assets twice in the past 10 years, a remarkable feat when the numbers are in the trillions. Growth has come organically and through well-timed acquisitions. BlackRock bought Merrill Lynch & Co.’s fund management unit in 2006 and Barclays Global Investors in 2009, which catapulted the firm into ETFs.

Blackstone, which turns 30 this year, has trounced its closest competitors. Its $48 billion market cap is roughly equal to all of its publicly traded private equity peers combined, including KKR, Carlyle Group and Apollo Global Management. Margins are higher in the alternatives realm, so Blackstone’s operating profit exceeds BlackRock’s, even though Mr. Fink’s pool of assets is an order of magnitude larger. After reporting 2014 adjusted income of $4.3 billion, about $1 billion more than BlackRock, Mr. Schwarzman boasted in a letter to investors that his firm was the world’s most profitable public asset manager.

Just because past successes have been on parallel tracks, however, doesn’t mean the search for growth isn’t forcing the firms to cross paths. Mr. Fink has been making forays into private equity, hedge funds and real estate. In 2009, BlackRock hired Matthew Botein to be co-head of this alternatives business, which now manages $113 billion. Mr. Botein once worked for Blackstone.

Both firms eye the huge opportunity in serving individual investors who, in the U.S. alone, control some $14 trillion in retirement savings.

In the past two years, Blackstone has launched two mutual funds, which invest in hedge funds and have collected $3 billion in assets. The firm is also offering private equity and real estate funds for wealthy retail investors and has created publicly traded credit funds.

“You’re seeing the traditional and alternative managers bump into each other,” says Rob Lee, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods who follows Blackstone and BlackRock.

SHARED HISTORY

Once upon a time, of course, Mr. Schwarzman and Mr. Fink and all of their employees were together in one office at 345 Park Ave. in New York. The shared history of Blackstone and BlackRock is the stuff of Wall Street legend. Mr. Schwarzman and Peter G. Peterson, former colleagues at Lehman Brothers, founded Blackstone in 1985, starting with just $400,000. They invented a firm name that melded their own names. (Schwarz is German for “black,” while Peterson comes from the Greek for “stone.”) The initial enterprise included merger advice, which was Mr. Schwarzman’s specialty at Lehman, and the nascent business of leveraged buyouts.

Mr. Schwarzman, now ranked 88th among the world’s richest people (worth $13 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index), at that time was in pure entrepreneur mode, cribbing resources where he could. He used corporate libraries at friends’ investment banks, including First Boston, where his pals Bruce Wasserstein and Joseph Perella worked. During his visits, he got to know a young employee named Larry Fink. When Mr. Fink left First Boston in 1988, Mr. Schwarzman and Mr. Peterson staked him and Mr. Schlosstein with $5 million to start a fund management shop at Blackstone. In Mr. Schwarzman’s telling, their business plan was written out on a roll of toilet paper. (BlackRock says it was a roll of paper from an easel.)

Mr. Schwarzman grew up in Philadelphia and showed an ambitious streak early. When he was 15, he told his father, who owned a housewares store, that he should expand his business into a national chain. His father rejected the idea, saying he was happy and had all the money he needed. His son couldn’t understand such thinking.

Mr. Fink was raised in Van Nuys, Calif., the son of a shoe salesman and an English professor. His drive was in evidence by the mid-1980s, when he was one of the pioneers of mortgage-backed securities. Just after his 33rd birthday, he made $100 million one quarter as a trader and lost more than $100 million the next — a formative experience and an episode that led to his eventual departure from First Boston.

Mr. Fink, who has a professorial demeanor, and Mr. Schwarzman, who is more bombastic, worked together for about five years. What became known as BlackRock Financial thrived from its earliest days and never raised additional money. But by 1994, with $23 billion in assets under management, a split was developing over how to grow the business. The Blackstone principals’ stake in BlackRock had already dwindled to 35% from 50% as Mr. Fink offered equity to attract employees. Mr. Schwarzman thought that was enough, but Mr. Fink wanted to give away more. In the end, they agreed to sell the BlackRock business to PNC Bank for $240 million. (PNC later spun BlackRock off and remains its biggest shareholder.)

“It was a very bitter divorce — but I don’t regret it,” Mr. Fink said in a 2011 interview with the New York Times. “I’m larger,” he added, a boast about his assets under management. (While Mr. Fink and Mr. Schwarzman say they pay little attention to each other’s business, executives at both firms can rattle off accurate, up-to-date comparisons of assets, earnings, market value and other metrics.) Mr. Fink and Mr. Schwarzman have reconciled, Mr. Fink told the Times. “I’ve never heard from any source in the world anything but praise from Steve about who I am and what BlackRock is.”

Indeed, Mr. Schwarzman says of Mr. Fink, “I have enormous admiration for him.” And he told Bloomberg in 2013 that letting BlackRock go was a “heroic mistake.” And yet people who know both men say their outsize personalities probably made it inevitable that they couldn’t coexist in a single organization.

So Mr. Schwarzman and Mr. Fink are not friends today, but they are friendly and bump into each other often enough on the financial statesman circuit. Politicians woo both men for counsel — and campaign contributions.

DEALMAKER OF THE CENTURY

On a typical day recently, Mr. Schwarzman met with Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor and Republican presidential hopeful. After he walked Mr. Bush out, Mr. Schwarzman sat for an hourlong interview for this story. Then he was out of his offices and into a black car to go to lunch with New York’s Democratic mayor, Bill de Blasio.

Mr. Schwarzman has played a political negotiator role at times. At the height of the 2012 showdown between the Obama administration and the U.S. Congress over the so-called fiscal cliff, he was a go-between for the White House and Eric Cantor, then the majority leader in the House of Representatives.

“The taxpayers were getting a great bargain — the dealmaker of the century trying to cut a deal for the president,” says Mr. Cantor, who became a vice chairman at the investment bank Moelis & Co. after losing his congressional seat. He says he took half a dozen phone calls from Mr. Schwarzman during the fiscal cliff standoff, which ended with compromise legislation at the last moment. Mr. Cantor remains in contact with Mr. Schwarzman, and he and Mr. Schwarzman both attended an off-the-record executive summit in March that helped to inform Mr. Fink’s CEO letter.

MACROECONOMIC GURU

Mr. Fink’s public role has a different emphasis than Mr. Schwarzman’s. With his fixed-income background and massive number of clients, Mr. Fink weighs in on monetary measures and financial stability issues. During the 2008 financial crisis, he spoke regularly to U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner. When the euro zone was teetering a few years later, BlackRock was an adviser to the governments of Germany, Greece and Ireland, among others.

“There’s a need for a voice for savers,” he said in a 2012 interview he did for consulting firm McKinsey & Co.

He’s also defended the disaffected little guy at times. When Occupy Wall Street protesters were commanding attention in 2011, Mr. Fink said that he understood why they spoke out against financial firms.

Mr. Fink’s letter in April decrying short-term thinking prompted a wide-ranging public discussion — and criticism from activists. Carl Icahn said Mr. Fink’s position emboldens underperforming CEOs.

“A lot of them feel like they can do what they want because of guys like Larry Fink,” Mr. Icahn said in an interview. As much as Mr. Icahn has clout when he invests in a target stock, BlackRock probably has more. The firm votes about 15,000 proxies a year and is often the biggest holder of shares of a given company.

FRENEMIES

Mr. Fink and Mr. Schwarzman share the global stage mostly without signs of friction. But in one area, the success of his former partner rankles Mr. Schwarzman: market cap. Despite Blackstone’s greater operating profit, BlackRock gets a higher valuation. The gap is about $11 billion lately. Investors give BlackRock a higher price-earnings multiple on the idea that the traditional money manager’s earnings are safer and steadier.

Mr. Schwarzman complains about this whenever he has the chance.

“People have some fear that if we sell things, we will never invest in anything ever again that will make money,” he said in May on Bloomberg television.

His 30-year track record should dispel such concerns, he said. Blackstone has been catching up with BlackRock of late, which may give Mr. Schwarzman solace — or encourage him to keep talking about the matter. Blackstone shares have climbed almost three times as fast as BlackRock’s in the past two years.

“The holy grail for the private equity firms is how do they get the big, long-only manager multiple,” Mr. Lee said.

For Mr. Schwarzman, reaching that loftier valuation might be one way to get over his regrets about having lost BlackRock — and Mr. Fink — all those years ago.

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.