T. Rowe Price’s Rob Sharps talks about investing for growth

T. Rowe's largest holdings in U.S. stocks are Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook.

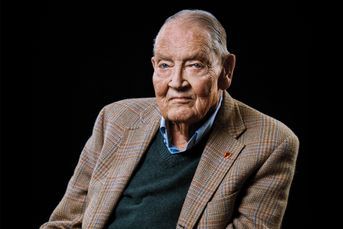

Rob Sharps is T. Rowe Price’s group chief investment officer. He ran the T. Rowe Price Institutional Large Cap Growth Fund (TRLGX) from December 2002 to March 2017. InvestmentNews spoke to Mr. Sharps about the stock market, energy and investing for growth.

John Waggoner: T. Rowe Price was founded as a growth shop. Where are you finding growth these days?

Rob Sharps: We’ve been big holders of disruptive companies that have a combination of financial resources, computing power, engineer talent, [and] big user bases that are pushing into a lot of industries across the globe and growing at a remarkable pace. Our five largest holdings in U.S. stocks are Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook. We’ve been longstanding owners of those companies. They’re also the five largest holdings of the S&P 500.

JW: Does it concern you that the market is so concentrated at this point?

RS: Not necessarily. I think market concentration often occurs later in the cycle. It’s not that unique. What’s unique is the traits that have allowed these companies to be successful. They’re all modern technology titans. If you look at points past, it wouldn’t be that unusual to have five companies make up that much of the S&P 500, but they would be companies like Exxon, GE and Pfizer, that don’t have those commonalities.

(More: T. Rowe Price steps up its game to serve financial advisers)

JW: When talking to clients about what to expect in the next five or 10 years, what do you usually say?

RS: I think investors need to have reasonable expectations. A lot of pension plans, which are very sophisticated, have return assumptions that are 7.5%, 8%. Many of those have allocations to equities that are below historical norms. When you start from an environment where the yield on the 10-year Treasury note is bouncing around 2%, 2.5%, and credit spreads are historically tight, it’s hard for me to understand how or where people are going to generate that asset-weighted 7.5% or 8% return, particularly when more and more are getting passive and not able to generate excess return.

Right now the outlook is pretty good. We’re in the middle of a global economic expansion that’s synchronized for the first time since the end of the financial crisis. Developed markets are growing, emerging markets are growing, China seems much more stable. You have relative stability and increasing prosperity in markets around the globe at the same time you have low inflation and a pretty good labor market.

(Watch: How T. Rowe Price is courting advisers)

Longer term, we have some meaningful challenges. Demographics suggest that GDP growth could be slower than what historical norms would be. You have a phenomenon of population growth being less than it was in the past, particularly in developed markets. Productivity growth has been much lower than you’d expect at this point in the economic cycle. And if you start from a level where asset prices are high, your going-forward return assumptions should be lower. There are a lot of things longer term we have going for us as a country, but we have a lot of things we have to address in terms of entitlements and infrastructure.

JW: Will automation be a net gain for GDP?

RS: I think so. Think about the music industry. As consumers of music, we’re clearly better off. For $12 a month, you have all the music in the world at your fingertips. You don’t really have to think about making a playlist: Pandora will just play, for the most part, things you’ll enjoy. But the industry has contracted. There’s psychic enjoyment we’ve gotten as a result of the innovation and progress we’ve made, but it’s caused GDP to contract. So is that a good thing or a bad thing? Measuring GDP purely on dollars might be the wrong measure. There are some offsetting measures of productivity.

I do think there are areas in terms of energy and transportation where there will be immense disruption. Think of the number of people who think of driving as their skill. Think about filling stations and the economy around the exits on the interstate system if driving becomes a shared service. And the ecosystems around cars: Electric cars don’t use oil, they don’t use oil filters, they don’t have exhaust systems; there’s much less wear and tear on brake pads. It will really change the nature of the ways things work. You have to focus on generating insight and getting the big things right, and those things will happen in transportation in the next five to seven years.

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.