Popularity of collateralized loan obligations widens thanks to demand from rich

Buyers have included affiliates of the Pritzker family, Bill and Melinda Gates, and the family office of Seattle Seahawks owner Paul Allen

Some of the world’s wealthiest clans have been throwing their money into an esoteric piece of financial engineering that has Wall Street in its thrall.

They’re called collateralized loan obligations, and they transform riskier company loans into bonds of varying risk and reward. Buyers have included affiliates of the Pritzker family, Bill and Melinda Gates, and the family office of Seattle Seahawks owner Paul Allen, who co-founded Microsoft Corp. with Gates. The Huizenga family behind the Waste Management Inc. empire as well as Iconiq Capital, which invests on behalf of wealthy clients including Facebook Inc. co-founder Mark Zuckerberg, have both had CLO exposure in their portfolios at some point. The Anschutz family, led by Los Angeles Lakers co-owner Philip Anschutz, is another player.

The presence of the hyperrich in deals underscores the widening demand for CLOs, a three-letter acronym that’s inspired fear and fervor in the debt markets this year. Proponents point to CLOs’ potential for double-digit returns, resilience to rising interest rates, and low defaults through last decade’s financial crisis. Others such as KKR & Co.’s Jamie Weinstein, however, have raised questions about whether the frenetic pace of sales is spurring reckless behavior just as the prospect of an economic downturn looms over an increasingly leveraged corporate America.

“It’s attractive from a total return perspective. It’s a robust structure,” said John Popp, global head and chief investment officer of Credit Suisse Asset Management’s Credit Investments Group. “You only have issues if you have a manager investing in a disproportionately high number of credits that default and have losses.”

The participation in CLOs by investors mentioned in this story was revealed by people familiar with the investors’ finances who asked not to be identified because the information is private. In some cases tax filings also disclosed the investments. The families’ wealth managers either declined to comment or didn’t respond to requests for comment.

CLOs are typically assembled by managers such as Blackstone Group’s GSO Capital Partners, the Carlyle Group and Ares Management, which buy loans that have been made to companies with a sub-investment-grade rating. The managers then package the loans into a structure that can be divided into interest-paying bonds and a chunk of equity. The income from the loan payments is paid to the bondholders in the order of their ranking within the structure, from the most senior and lowest-yielding to the most junior and highest-yielding. The equity is last in line, making it the riskiest but also the most potentially lucrative piece.

It’s that last part, the equity chunk, that’s been of particular interest to family offices, say CLO managers and investors including Tricadia Capital Management and Investcorp Credit Management US. Returns on CLO equity can range from 12% to a remarkable 20%, standing out in credit markets where corporate bonds have delivered little or negative returns this year.

Family offices “make an ideal investor in the less liquid part of the CLO because of their ability to hold the investments through maturity, as well as their ability to withstand volatility that public companies or insurance companies may have a hard time dealing with,” says Michael Barnes, co-chief investment officer at Tricadia.

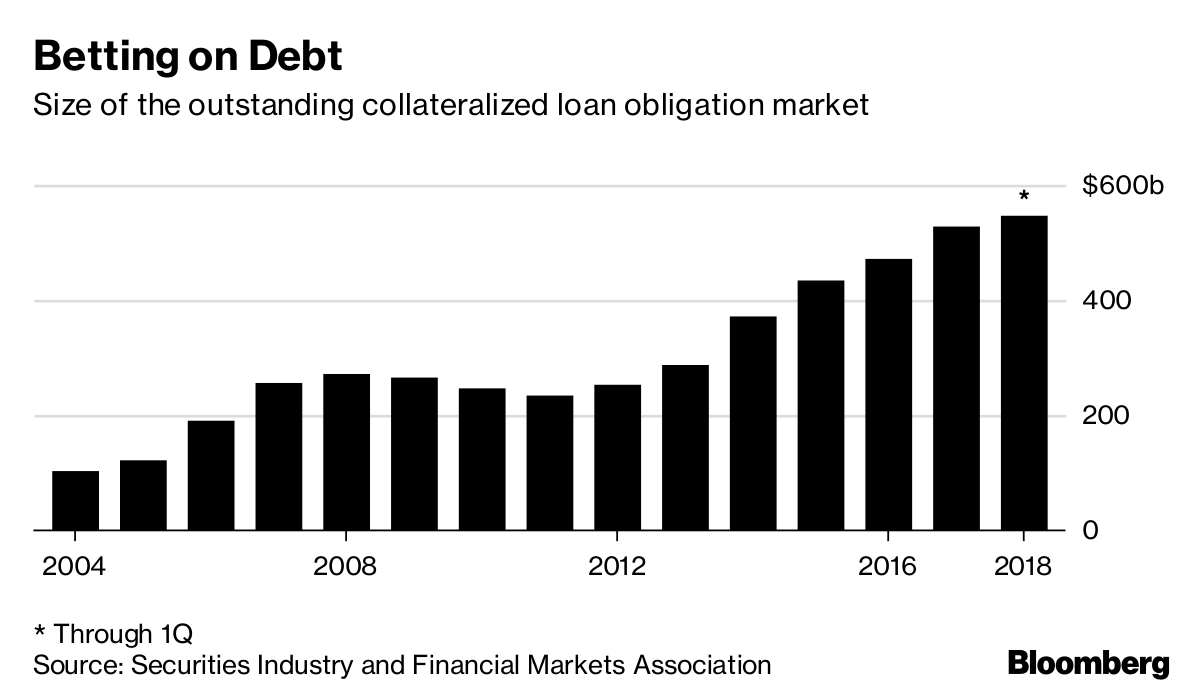

Their investment is helping fuel growth in the U.S. CLO market, which had some $540 billion in deals outstanding at midyear, up from about $250 billion in 2008.

Demand accelerated because both the CLO bonds and underlying loans are “floating rate,” meaning they pay more yield as interest rates rise.

Some banks lifted their sales forecasts to fresh highs after a rule that made CLOs more expensive to assemble was repealed this year.

Known as the skin-in-the-game rule, it had been credited with helping the market expand. It required CLO managers to buy pieces of their own deals to dissuade them from selling bonds backed by shaky loans. Managers often borrowed money to finance their own position in the deal, and the effort to win that financing amounted to a global marketing exercise that educated investors, including family offices, on CLOs.

“It’s been quite dramatic,” says Maureen D’Alleva, head of performing credit at Angelo Gordon & Co., referring to the pickup in CLO demand. “CLOs have seen an increase in the overall pool of investors from pension funds to family offices.”

For some, the fast growth has recalled the subprime crisis, in which demand for high-yielding credit fueled the creation of debt structures stuffed with low-quality loans. Those in the industry say CLOs are different because the underlying loans to companies aren’t as vulnerable to rising interest rates as subprime home borrowers were a decade ago. Among the 1,500-plus U.S. CLOs rated by S&P?Global Ratings since 1994, only 36 tranches across 21 transactions had defaulted as of mid-2018.

Of course, similar arguments were made before the subprime debt collapse about the historical resilience of mortgage debt. “Securitization is not alchemy,” Boaz Weinstein, chief investment officer and founder of hedge fund Saba Capital Management, says in an interview with Bloomberg Markets. “People think credit spreads are too low, yet they love CLOs. Hard to hate the pie and love the pieces. The equity tranche offers a double-digit yield, but a real pickup in defaults will bring losses.”

For family offices, investments in CLOs are part of an increase in allocations to alternative investments as they diversify holdings, according to David Scott Sloan, co-chairman for global private wealth services at Holland & Knight. Pioneered by John D. Rockefeller, family offices have mushroomed in recent years as a growing number of wealthy families seek more active involvement in managing their fortunes.

CLOs originated in the late 1980s, and family offices have been investing in them for more than a decade. The Pritzkers, the family behind the Hyatt hotel chain, were among the early investors in this space. Pritzker Foundation tax filings for 2015 and 2016 show it invested in the equity of a Hildene Capital Management CLO.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Trust has invested in CLOs managed by BlueMountain Capital Management, BlackRock Inc., and others, 2015 and 2016 filings show. Representatives for Hildene, BlueMountain, and BlackRock declined to comment.

“CLO equity has been a hot product,” says Sean Solis, a securitization attorney and partner in New York for Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. “High-net-worth investors through banks as well as family offices have shown up more and more in minority positions in CLO equity.”

Family offices tend to come in for smaller chunks, worth from $5?million to $15 million, alongside bigger investors such as hedge funds, Mr. Solis says.

CLO equity starts producing cash flow within six months of a deal closing and makes “an ideal investment for those who understand the risks and are willing to commit their capital for a long period,” says John Fraser, head of Investcorp Credit Management U.S., which manages assets including CLOs.

Not everyone has overcome the trauma of the financial crisis, which featured the collapse of credit products with initials such as SIVs and CDOs. “There are still a lot of investors that shy away from CLOs,” Credit Suisse’s Mr. Popp says. “The acronym aversion is fading, but it’s still there.”

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.