The October edition kicks off with the big news that Franklin Templeton is acquiring O’Shaughnessy Asset Management and its Canvas direct indexing platform, as yet another traditional asset manager makes a bet that the future will be increasingly driven by direct indexing rather than traditional mutual funds and ETFs. Notably, though, OSAM’s Canvas wasn’t simply another platform to turn an index fund into one where its component stocks can be tax-loss harvested for incremental tax alpha; instead, it was part of a second generation of direct indexing platforms that are building tools for advisers to create increasingly personalized “custom indexes” for each client based on their own individual preferences … where the asset manager can get paid as a separate account manager to implement those unique-to-each-client portfolios?

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting adviser technology announcements, including:

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, as well as a discussion of more trends in adviser technology, including:

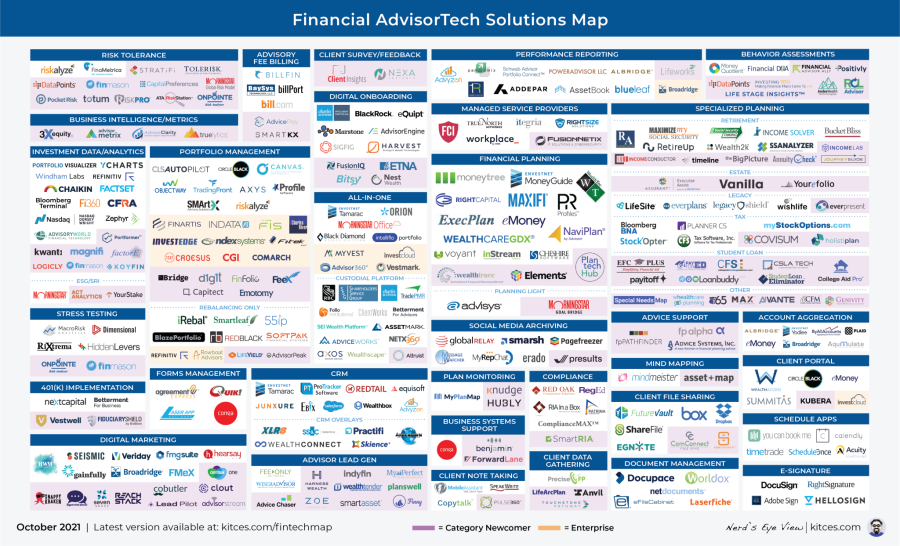

Be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map as well!

#AdviserTech companies that want their tech announcements considered for future issues should submit to [email protected]!

When direct indexing first emerged more than 20 years ago, it was an investment strategy built around generating tax alpha for ultra-high-net-worth clients by owning the component stocks of the index to allow them to harvest the losses of the individual components of a stock index even if the index itself was up. For instance, if the S&P 500 grew 12% for the year, but 137 stocks within the S&P 500 were down (while others rose enough to net 12% overall for the index), a direct indexing strategy would harvest losses in the 137 stocks that were down (generating some immediate tax savings) and simply hold the rest. That contrasts with an S&P 500 ETF or mutual fund, where if the fund was up 12% for the year, there would be nothing to tax-loss harvest.

However, the first generation of direct indexing players — like Parametric and Aperio — were largely focused on the traditional channel of HNW clients, largely because it took a sizable portfolio to be able to break down the S&P 500 into its individual components and still be able to own the proper allocations in whole shares (because fractional shares were not yet widely available). This changed in 2014, though, when Wealthfront launched its Wealthfront 500 strategy to democratize direct indexing for more mainstream investors (with a mere $500,000 minimum that soon dropped to $100,000 for an only slightly narrower Wealthfront 100 strategy), as the rise of fractional share trading via platforms like Apex (and more recently, the collapse of trading commissions to zero), combined with the model management capabilities of the first crop of robo-advisers, made it feasible to bring direct indexing down from HNW investors to the mass affluent.

In the years that followed, a new wave of second-generation direct indexing platforms emerged, including JustInvest, OpenInvest, Ethic Investing, and Vise (among others). What made these second-generation solutions unique was that while Parametric and Aperio were first and foremost asset managers that offered a particular direct indexing asset management strategy (that began to implement and scale direct indexing with technology), the second-generation firms were built as tech companies to offer a tech solution of making direct indexing configurable for whatever the investment manager wanted — whether an adviser or a consumer managing themselves.

Which meant that not only could the second generation of direct indexing platforms potentially offer any index they wanted — not just a particular S&P 500 strategy — but advisers could potentially implement any strategy they wanted on a direct indexing chassis, from DFA-style factor investing to a filter-based SRI strategy or implementing various ESG under- and over-weightings or whatever other preferences the clients wanted to see expressed in their portfolio (or even customizing the client’s portfolio around their existing holdings or industry exposures). In other words, technology began to turn direct indexing into more fully customized and personalized indexing.

Now last month, traditional asset manager Franklin Templeton announced the acquisition of the second-gen direct indexing platform Canvas, built by O’Shaughnessy Asset Management. Canvas was one of the more recent entrants to the second-gen direct indexing category, launching at the end of 2019, but it had experienced rapid growth in the adviser community, driven in part by O’Shaughnessy’s existing ties to advisers through its own asset management solutions (as a $6.4 billion asset manager itself), and high-profile adviser adoption from influencer firms like Ritholtz Wealth Management, which allowed OSAM’s Canvas to grow to more than $1 billion in barely a year (and reportedly nearly $2 billion after not even two years).

Notably, though, while technology is increasingly making it feasible for advisers to implement any kind of customized “indexing” portfolio on a client-by-client basis (though with full customization for each client, it’s hard to even call it “indexing” anymore?), implementing the trading of those portfolios — and the high volume of individual stock purchases and sales that must be executed in the era of payments for order flow and high-frequency traders — is still challenging. Which is why, in practice, direct indexing solutions are often being sold not as a pure tech offering, but instead as a separately managed account run by an asset manager that implements the trades based on what the adviser requests through the direct indexing technology’s portfolio construction process.

In that vein, the irony is that direct indexing — and its increasingly personalized indexing cousin — may still look like a fairly traditional SMA offering to the industry and align well with Franklin Templeton’s existing $130 billion SMA business. But the adviser move to more personalized indexing is a much more profound shift in the industry itself. Because the reality is that if personalized indexing technology increasingly becomes the framework for portfolio design for advisers — built around a chassis of individual stock trading — it dramatically reduces the need for advisers to purchase mutual funds or ETFs, potentially shifting trillions of dollars of adviser flows (a change broker-dealers and custodians would likely welcome, as their economics from securities lending to payments for order flow are far better when advisers trade the 500 stocks of the S&P 500 rather than one index ETF!).

Of course, the big question is simply whether advisers will adopt direct and increasingly personalized indexing, in a world where almost all adviser platforms can now handle fractional shares and execute with zero trading commissions. But as advisers increasingly struggle with differentiation, personalized indexing is arguably both the ultimate differentiator, at least with respect to investment management services (as every client’s portfolio is different and customized for them!?). Not to mention that personalized indexing also helps advisers get out of the performance game (because when every client’s portfolio is unique to their individual preferences, it’s almost impossible to benchmark the adviser’s performance because the portfolio was shaped by the client’s preferences). Which helps to explain why platforms like OSAM’s Canvas grew to almost $2 billion in under two years, and why Franklin (along with Sequoia and Ribbit Capital in their eye-popping $1 billion-plus valuation of Vise) seems to be betting that’s only just the beginning.

One of the most dominant investment shifts of the past decade has been the transition from mutual funds to ETFs, and the associated proliferation of index investing. Notably, the shift toward more index-based ETFs doesn’t necessarily mean that financial advisers are going “passive” — as in practice, a growing number of advisers are simply actively managing those index ETFs, such that the rise of ETFs is less about a shift from active to passive, and more simply a shift to advisers managing client portfolios more directly (rather than outsourcing to mutual fund managers) and making indexes the building blocks they use to manage their asset-allocated portfolios.

On one hand, this rise in advisers insourcing their active management strategies is helping to spur ever-growing levels of adviser portfolio construction and customization — most recently, with the rise of direct indexing. On the other hand, though, the shift toward using index-based ETFs as portfolio building blocks is also creating a growing focus on the indexes themselves, which indexes are being used, how they are constructed… and for the ETF providers offering those index ETFs, the underlying cost to license those indexes in the first place.

In this context, it’s notable that last month Morningstar announced the acquisition of Moorgate Benchmarks. For those who aren’t familiar with Moorgate, it’s a global provider of index design, calculation and administration. And the acquisition of Moorgate will provide Morningstar with further capabilities to create ever more unique and customized indexes for asset managers who want to build ever more unique and differentiated index ETFs. With the caveat that when every index is unique and differentiated, arguably it’s not really even an index anymore… it’s simply a custom-designed portfolio, albeit one that Morningstar may have a hand in constructing, implementing and licensing on a centralized basis across the industry.

In other words, while the recent focus on direct indexing has been all about creating increasingly customized and personalized portfolios — down to the individual client level — as a means of disrupting the ETF or mutual fund market as we know it, Morningstar seems to be making a bet that at least some direct indexing will be expressed not in client-customized portfolios, but simply in the form of increasingly unique indexes that Morningstar can design and license via direct index providers to advisers… a kind of model marketplace approach where Morningstar wouldn’t necessarily have to manage the portfolio (SMA-style) to get paid, as it could simply license the customized index that another SMA (or advisory firm themselves) pays to implement themselves.

In fact, Morningstar directly called out traditional index providers in its press release about the acquisition, stating that traditional index providers are not keeping pace with innovation. It seems that Morningstar would like to take on that burden itself.

Ironically, though, with the pace of the large entrenched asset managers acquiring this technology at lightning speed, the question arises as to whether much of anything will actually be disrupted in the industry, or if incumbents moving into the direct indexing space with various strategic approaches (from licensing indexes to implementing direct indexing via SMAs) are sufficiently defending their castles and rebuilding their moats, to the point that these new offerings will simply become another feature in the bag carried by asset manager wholesalers?

When robo-advisers first showed up nearly 10 years ago with the vision of replacing human financial advisers with slick technology that could easily onboard new clients and implement their chosen (model) portfolios, most financial advisers didn’t look at the technology and say, “That’s a threat to my business,” but instead looked at the tech and said, “I wish my firm could onboard clients that easily, too!” In other words, at the most basic level, robo-advisers weren’t a threat to human advisers because the robos didn’t actually do what human advisers do in the front office with clients. Instead, they were an upgrade to the typical adviser’s back-office systems.

Accordingly, in the years that followed, a growing number of robo-advisers that struggled in (or didn’t even want to compete in) the hyper-competitive direct-to-consumer channel with its high client acquisition costs pivoted instead to become robo-advisers-for-advisers, making their technology available to streamline an advisory firm’s back-office onboarding workflows, including FutureAdvisor, Jemstep, AdvisorEngine, RobustWealth and more. Such firms aptly recognized how outdated the average adviser’s onboarding capabilities were relative to what technology was capable of delivering (and robo-advisers had proven could be done).

The caveat, though, is that while financial advisers were largely frustrated with and in search of upgrades to their own onboarding experiences with clients, the ability to make those upgrades was limited by the capabilities of broker-dealers and custodians to be able to connect with and handle the straight-through processing requests of the various onboarding tools. While advisers themselves increasingly balked at paying a separate fee to the robo-platforms just to upgrade the lacking onboarding capabilities of broker-dealers and RIA custodians, and instead increasingly just demanded that the platforms upgrade themselves and become better for the advisers that use them.

The end result of this trend was that adviser platforms began to increasingly acquire or build to bring their rob” tech in-house, from RIA custodians who built their own “digital account opening wizards,” to various asset managers that acquired their way into the technology (e.g., BlackRock acquiring FutureAdvisor, Invesco acquiring Jemstep, WisdomTree and then Franklin Templeton acquiring AdvisorEngine, Principal acquiring RobustWealth, etc.). They effectively turned digital onboarding capabilities into a tech value-add for their adviser platforms or asset management solutions, as opposed to a stand-alone software solution unto itself.

In this vein, it’s notable that in September, TAMP provider First Ascent announced the acquisition of Fast Forward, which was a digital onboarding tool that was originally built for and licensed to First Ascent and will now be fully owned by the company.

The transaction is notable not only because First Ascent, like many TAMPs, continues to see the quality of its digital onboarding tools as an opportunity to differentiate in a crowded TAMP marketplace (which, notably, included not only the core account opening functionality, but also a broader front-end for advisers with their prospective clients, including a risk tolerance assessment and proposal generation tool), but also because it highlights the limitations that RIA custodians face in trying to build their own digital onboarding experiences.

Because as the value-adds of TAMPs increasingly go beyond just the portfolio management capabilities themselves (as investment strategies can be served up in any number of mediums, from model marketplaces to strategist overlays to SMAs and UMAs) and into the technology and service layers that support the adviser, the need for workflow efficiencies and business process automation go beyond just the processes of account openings and transfers, and instead span the full breadth of services the TAMP provides, and a broader technology stack that supports it (most notably, the TAMP’s own CRM system and workflows for servicing their advisers and clients).

In other words, a distinction is emerging between the digital onboarding experiences for investment accounts themselves — the domain of robo-advisers (or more generally, tech-savvy direct-to-consumer asset managers) and RIA custodians and broker-dealers (which facilitate the account openings and transfers) — and the digital onboarding of those providing value-added services beyond portfolio management (from TAMPs servicing their advisers as First Ascent acquires Fast Forward, to advisers servicing their own clients as Docupace acquires PreciseFP), that is leading to a demand for a separate additional layer of onboarding tools, not simply to facilitate the movement of assets, but the servicing of an entire relationship (and to manage the data and workflows across the multiple systems it takes to service those relationships).

The appearance of robo-advisers a decade ago created a striking dichotomy in the ongoing evolution of the financial advisory business. On one hand, the arrival of technology to automate the implementation of low-cost diversified portfolios drew a fresh line in the sand — at approximately 25 basis points of cost — that said, “If advisers are going to charge their 1% AUM fees, they have to deliver 75 bps of value above and beyond what a robo-adviser can provide,” creating pressure to craft more unique and customized portfolios for their clients. On the other hand, such robo tools also became an opportunity for advisers to automate and outsource more of their portfolio management services, to free up more of their time to add value in other ways beyond the portfolio.

The distinction between the two paths is significant, because advisers who are seeking to add value beyond the portfolio will increasingly tilt toward portfolio management solutions that provide simpler portfolios that can be automated through outsourcing (because the portfolio literally isn’t the value proposition), while those trying to add value within the portfolio will seek tools that provide greater levels of differentiation for clients (e.g., the customization and personalization of adviser-built models, direct indexing, etc.) and require increasingly more capable custodial platforms to support those new investment management approaches.

Arguably, in the long run, the arc of financial advice is increasingly shifting toward more comprehensive advice, and advisers who add value beyond the portfolio rather than within (if only because sustainable outperformance is difficult for any adviser to achieve on an ongoing basis). Which is why platforms like Betterment were able to gain early traction with at least a subset of advisers, by taking their simple automated asset-allocated portfolio solution for consumers and making it available as a pre-built TAMP-style offering for advisers.

The caveat, though, is that the bulk of adviser assets are still with advisers who look to add value within their portfolios, and Betterment struggled to gain wide adoption with a platform that was built first and foremost to implement its own Betterment model portfolios — where most advisers simply didn’t feel comfortable charging clients to put them into portfolios that were identical to what those clients could get from Betterment directly without the adviser’s involvement. That led Betterment down the path of making its platform increasingly flexible for advisers who want to differentiate with their portfolios, from offering third-party models beyond Betterment’s own (e.g., from Goldman Sachs to Vanguard and BlackRock to DFA), and earlier this year rolling out a feature to allow advisers to build their own entirely custom model portfolios from the nearly 1,500 ETFs that Betterment is built to trade.

Now, Betterment has announced that it is expanding its Custom Model Portfolios capabilities, offering the service to any advisers who are interested (and waiving what was previously a $2.5 million adviser minimum to set up a custom model on the platform). Notably, though, Betterment has indicated that it does not intend to expand its Model Marketplace as other adviser platforms have done in recent years, and instead is hoping to attract advisers away from other RIA custodians by showing them how they can (re-)build their existing ETF models entirely on Betterment’s platform.

From the Betterment perspective, making the platform more appealing to existing advisory firms that have built their value propositions around their investment management offerings is certainly logical, simply because that’s where the dollars are — especially given that Betterment itself is still ultimately operating on the AUM model, which means it needs to go where the money is. With trillions of dollars on competing RIA custodial platforms — and even more at play as brokers transition to the RIA model and put money in motion — Betterment increases its near-term market opportunity by being able to compete more directly with existing RIA custodians with more granular levels of portfolio construction tools.

From the broader industry perspective, though, it’s difficult to see where or how Betterment can create a sustainable differentiator by making itself more custodian-like. In practice, Betterment’s onboarding experience — where it first shined as a direct-to-consumer robo-adviser — still shines compared to most traditional platforms, but the rise of digital account opening wizards and more straight-thru processing capabilities mean traditional platforms are catching up (albeit slowly) to Betterment’s tech-onboarding differentiator. And in the end, if the core value of the platform is to allow advisers to build whatever portfolios they want, Betterment will likely still struggle with its limits on holding primarily just ETFs, and not the full range of stocks, bonds, mutual funds, alternatives and other investments that advisers typically buy their clients (that can already be easily accessed on any other traditional RIA custodial platform). Especially since Betterment still charges for a platform that other RIA custodians continue to give away “for free.” While ironically, Betterment was arguably well positioned in the market for advisers who don’t want to be portfolio-centric and simply needed a place to fully outsource their client portfolios in a simple and digitally convenient manner for clients… even if that was the (much-smaller) adviser segment where Betterment could shine?

For several decades now, a growing body of research into behavioral economics has identified an ever-widening series of behavioral biases that lead investors to make various investment mistakes, from the recency bias (over-projecting recent trends into the indefinite future) to loss aversion (tendency give the pain of losses more weight than the joy of equivalent gains) to overconfidence bias (we often think we’re better at investing than we actually are).

Yet while these biases and investing blind spots can lead us to unwittingly make undesirable investment choices, in recent years a more positive approach has recognized that systems can be designed in ways that help leverage our biases for our benefit as well, exemplified by books like Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s “Nudge.” For instance, it turns out that it really matters whether choices are presented as opt-out or opt-in (since we have a status quo bias to stick with the default choice, making the desired choice a default-in opt-out increases the likelihood of selection and follow-through!) and it’s possible to help people save more tomorrow by getting them to precommit to saving more in the future (which leverages our tendency to discount the future by making the pain of savings less painful by pushing it into the future).

However, in practice, there’s often a fine line between using nudges to persuade people to do what’s in their interests (that they probably should be doing anyway) and manipulating them into doing what’s in the nudger’s own interests. That’s leading to a fresh wave of scrutiny regarding the way various fintech solutions — from trading platforms like Robinhood to robo-advisers like Betterment are using technology nudges to influence the behavior of their investor users.

Notably, the SEC’s inquiry isn’t meant to imply that there’s anything wrong with giving nudges to investors. After all, a broker who outright solicits their client to buy a particular stock is doing far more than just nudging their client with such a recommendation. And investment advisers are often outright engaged to give advice on exactly what their clients should do — or are even hired not just to nudge them to do it, but actually do it for them(in the form of a discretionary managed account).

The distinction, however, is that providing a recommendation or outright advice is subject to specific standards of care — Regulation Best Interest for brokers providing the former, and the fiduciary standard of care for investment advisers offering the latter — while the compliance obligations are more limited for self-directed trading platforms that just facilitate their customers’ unsolicited orders.

Which means the concern is not whether there’s anything improper about nudges, per se, but that it is necessary to determine when a nudge is not just an administrative or user convenience, but when a “digital engagement practice” (or DEP, as the SEC is terming it) may constitute a “recommendation” (subject to Reg BI) or “advice” (triggering registration as an investment adviser, and the attendant fiduciary duty).

In addition, the SEC notes additional concerns related to investment advisers in particular, where a purely digital engagement experience may fail to maintain sufficient ongoing knowledge of the client’s (potentially changing) circumstances, which could result in advice that was once appropriate but is no longer (that the nudge-only, limited-human-interaction platform might fail to identify).

More generally, the SEC’s inquiry into digital engagement practices also highlights the agency’s rising focus on the conflicts of interest that may be exacerbated when nudges drive customers — potentially unwittingly — toward more costly outcomes. That aligns with the recent Schwab announcement of an anticipated $200 million charge to its earnings associated with an SEC investigation into its Schwab Intelligent Portfolios robo-adviser platform that was by nudge-default allocating customers heavily into Schwab ETFs and Schwab’s affiliated-bank cash sweep program.

In the end, though, perhaps the most notable aspect of the SEC’s inquiry is that the regulator is not necessarily suggesting that it’s time for any new rules when it comes to the rise of fintech and its increasingly common nudges and other digital engagement practices. Instead, the focus of the SEC’s questions is exploring how fintech fits within the existing framework of brokers and their recommendations, RIAs and their advice, the lines of when a recommendation versus advice (versus neither) is provided, and the disclosures that are provided when nudges nudge customers in a direction that represents a conflict of interest for the fintech nudger.

Fee-only financial advisers evaluate product recommendations for clients in a fundamentally different manner than brokers and insurance agents. At its core, the driving difference is that brokers and agents are in the business of selling and distributing products, which means their business economics are driven directly by the commission on the sale (and may be influenced by certain companies offering higher commissions on their products than others), and indirectly can be influenced by what products their own platforms have selling agreements to offer in the first place (which in turn is usually driven by the availability of commission overrides for those intermediaries). In contrast, fee-only advisers are paid advice fees by their clients, so their core incentive is simply to compare the available products in the marketplace and implement whichever is most compelling and valuable to their end client.

As a result, the shift in advisers from broker-dealers and insurance companies to (fee-only) RIAs is driving a substantive shift in how various investment, and especially annuity, products are distributed. Traditional sales-based annuity distribution was driven primarily by selling agreements through IMO, broker-dealer and other platform intermediaries, with an army of wholesalers to explain the features and benefits of their products and train brokers and agents on how to sell them. Alternatively, an adviser could call their platform with a “case” about the client, and then a product would be recommended for the adviser to sell. But the reality is that this process was hardly scientific or quantitative. People have biases and those biases come through on recommendations, especially if a certain product is paying a higher commission that month! By contrast, RIAs most commonly want to do their own research evaluating and comparing products, and then be able to reach the companies to get their questions answered on their own terms.

To address this emerging opportunity in the marketplace, Luma Financial Technologies this month announced a new Luma Compare tool — an extension of its existing tools for evaluating structured products — which will allow independent advisers to objectively compare and evaluate a wide range of potential annuity products, including variable annuities, fixed-index annuities and registered index-linked annuities, rather than being constrained to a single wholesaler promoting a particular product. Which advisers can then also implement via the Luma platform.

More generally, the Luma Compare launch comes in the midst of a lot of movement occurring in the annuity space right now to help make annuities more discoverable (and understandable, and for fee-only advisers, more affordable) by eliminating the traditional commission structure that can’t be paid to RIAs anyway. The question increasingly is shifting away from “Will RIAs ever use annuities” and toward “What is the right model to help RIAs put the right annuities into the hands of the right clients who genuinely need them?”

The answer on “What is the right model” is still very up in the air. On the one hand, there are companies like Luma and its Compare tool, along with others like Simon Markets and Envestnet’s Annuity Exchange, that are trying to create technology tools that form a kind of discovery platform where advisers can search and find the right annuity products (and then purchase them on the spot, akin to an Amazon for annuities). On the other hand, there are those taking the outsourced insurance desk approach, like DPL and FIG’s RIA Insurance Solutions, which are focused on a more education-and-service approach to support RIAs. Others, like Signal Advisors, are in the middle, operating more akin to the traditional IMO but building the technology to function as a digital IMO for advisers.

It’s a well-documented problem that baby boomers are approaching the decumulation phase at blistering speeds and have a wide range of preferences for the various types of retirement income solutions that are available. The challenge is that, historically, industry channels separated annuities (which were agent- and broker-sold) from portfolio-based solutions (which were implemented by RIAs). As products shift to become more channel-agnostic, the tools and platforms necessary to facilitate that distribution are changing, which is opening up a very large RIA marketplace to annuity companies with products that at least some clients of RIAs will likely be interested in. Every tool that is created to help ensure that it’s the right product for the right client is a welcome addition to the marketplace, though it remains to be seen which marketplace solution in particular (more tech-based like Luma or more service-based like DPL) will gain the most traction with advisers.

While the registered investment adviser has existed since the 1940s — after being statutorily created by the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 — it wasn’t until the 1990s that the independent RIA business model truly gained traction. Up until that point, advisers who offered the traditional services as an RIA — managing individual client portfolios on an ongoing basis — typically worked with only a small subset of ultra-high-net-worth households, because it was extremely labor-intensive (or outright administratively infeasible) to work with more than a handful of clients at a time — which meant they had to be very affluent to generate enough revenue from a limited clientele.

What changed in the 1990s was the rise of RIA custodial platforms — starting with Schwab Advisor Services, followed shortly thereafter by Ameritrade Institutional, Fidelity Institutional, and a handful of others — that gave advisers a central platform from which they could execute the key workflows of the independent RIA model and perhaps even more importantly, collect their assets-under-management fees for the services rendered. Because in the end, it doesn’t matter how scalably a firm can deliver its services if it doesn’t have a scalable way to get paid for the work it has done. In turn, as the RIA custodians made it more administratively feasible for the independent RIA to scale the AUM model, advisers worked with an ever-widening range of clientele (who were now more accessible to serve), and the RIA flourished.

Now, as financial advisers increasingly shift toward providing portfolio management services for an AUM fee and increasingly comprehensive financial planning on a fee-for-service (e.g., hourly or project, monthly subscription, or quarterly or annual retainer) model, the question is once again shifting from “Will consumers engage with this new service model” to “How does a large and growing financial services enterprise scale the workflows for its advice delivery… and the means to get paid for it?”

To this end, AdvicePay this month announced the launch of a new Engagements solution, which, similar to Schwab and the other RIA custodians of the early 1990s, aims to provide the complete end-to-end infrastructure for advisers — and especially adviser enterprises — to support the scalable delivery of fee-for-service financial advice.

At its core, AdvicePay’s Engagements for Enterprises takes the underlying components of the system — Agreements (where prospects e-sign the advisory agreement to become a client), Payments (where clients are invoiced and pay their advice fees electronically via their credit card or bank account), and Deliverables (where it’s verified that the client received the financial planning deliverables that were promised to them under the agreement in exchange for the payment) — and wraps them into customizable Enterprise workflows to allow a large-scale enterprise to manage and oversee the entire advice engagement from start to finish. That’s important not only for the scalability of delivering advice itself, but for preemptively addressing the key compliance issues that regulators are increasingly scrutinizing (e.g., did the enterprise actually ensure that the deliverable was provided to the client before the client’s fee was remitted to the adviser, to ensure there was not a “fee-for-no-service” scenario).

From the adviser perspective, the appeal of AdvicePay’s Engagements is that large-scale enterprises (including Cetera, Financial Services Network and Thrivent Advisor Network) are increasingly showing a willingness to support the fee-for-service model to serve clients, now that technology is making it more feasible to do so in a scalable manner. That means advisers who had wanted to expand into various fee-for-service business models in the past — only to be told by their enterprises that they weren’t permitted to, because it wasn’t profitable for the enterprise to support — will now increasingly find their firms more amenable to allowing them to expand into new services and reach new clientele (as there are fewer and fewer AUM prospects who are not already attached to a financial adviser!).

From the broader industry perspective, though, the real significance of AdvicePay’s Engagements is that just as the rise of the first generation of RIA custodians in the early 1990s catalyzed the growth of the independent RIA’s niche AUM-for-HNW-clients model to take over from the previously dominant commission-based model, so too is AdvicePay increasingly positioned to catalyze the shift from the dominant AUM paradigm to turn the small niche model of charging stand-alone and ongoing advice fees into the next big business model for financial advisers.

While electronic imaging that’s able convert a paper document into a digital one has been around since the 1980s, it wasn’t until the rise and mainstreaming of the internet in the 2000s that the conversion from paper files to digital files really began to gain traction. The blocking point in the early years was that while a scanner could turn a paper file into an electronic version, it often wasn’t very practical for the firm — especially a larger enterprise with multiple locations — because the digital version of a file stored on a physical computer in an office in another location wasn’t much more accessible than the paper file in the first place. It took the interconnectivity of the internet to make a digital version of a file more accessible than the paper format — as centralized (and eventually entirely cloud-based) servers meant anyone, anywhere, could access the electronic version of the file.

Still, though, widespread adoption of the paperless office approach has been slow, in large part because scanning and cataloging paper files into a digital format are still slow, time-consuming, and relatively labor-intensive, aided only slightly by the rise of high-speed volume scanners to add the paper files more quickly, and optical character recognition to make it easier to identify and catalog them more quickly. In other words, the benefits of going from a papered office to a paperless office were still limited by the constraints of how paperwork was handled in the first place.

But over the past decade, the rise of “digital onboarding” — where there is no paperwork to be scanned in the first place, because the file is in the digital format from the very beginning — has begun to fundamentally change what’s possible in a paperless office. When business processes don’t rely on physical paperwork in the first place, not only does it eliminate the steps of scanning and cataloging (and the hassles and potential errors that go along with it), but when the business process shifts from moving paperwork to moving the information on the paperwork via APIs, it becomes possible for entire business processes to be fully automated as the key data are transmitted through each step of the process.

This shift from being merely a merely paperless back office to an entirely digital back office has driven two key trends in the world of AdviserTech.

On the one hand, it has created a hunger among financial advisers for more digital onboarding capabilities, and a shift away from just e-signing a document (which is still a paperwork approach, albeit in electronic format) to the use of “account opening wizards” and the like that capture the key data and transmit it to all the places it needs to go. That both expedites onboarding — with the potential for straight-thru processing — but reduces the redundancies of data entry, as no one needs to scrape the key client information off the electronic paperwork and put it into the CRM system, financial planning software, etc., but instead can simply have the data entered once and then ported everywhere it needs to go.

On the other hand, the shift to an increasingly digital back office has created an opportunity for what were traditionally paperless office providers (who handled digital document management, from storage to cataloging) to shift into the world of business process automation, increasingly tying business workflows to the electronic paperwork, and as the paperwork itself (physical or electronic) fades into the background, to increasingly become the handlers of the business processes workflows themselves and the warehousing and transfer of key data from one system to the next.

In this vein, it is perhaps no surprise that in September, Docupace (a popular provider of document management systems for adviser enterprises, and an early player in the transition from the paperless back office of electronic documents to the digital back office of business process automation) announced the acquisition of PreciseFP (an independent provider of digital onboarding that was known for its flexibility in plugging a single onboarding experience for clients into multiple different adviser software solutions, from CRM systems to financial planning software to RIA custodial platforms).

From the Docupace perspective, acquiring PreciseFP brings not only the flexibility of the company’s digital onboarding capabilities and its various integrations, but what was a primarily small-to-midsize independent RIA user base to Docupace’s historically large-broker-dealer-enterprise clientele, making the transaction one of both capabilities (as PreciseFP’s front end utility is plugged into Docupace’s back-end enterprise systems), but also of market expansion (as Docupace seeks to grow its footprint in the independent RIA channel).

From the broader industry perspective, though, the real significance of the Docupace/PreciseFP transaction is simply the recognition that as digital onboarding experiences make paperwork disappear entirely — whether in physical paper or electronic format — and reduce onboarding to the pure data itself and all the places it has to go to execute key business processes (from client onboarding to account opening and transfers to constructing a financial plan and more), there is a fundamental shift underway to an increasingly automated back office (as while robo-advisers were never really a threat to financial advisers, they are a threat to and will slowly replace the back-office support jobs in advisory firms). Docupace appears increasingly well positioned to capitalize on that with its PreciseFP deal.

Every wealth management client needs an estate plan, but, in practice, many clients have never gone through the process of establishing their wills and trusts and setting a plan for what happens to their assets after they die. Even those who have rarely update it often enough to remain timely. Yet, in practice, it has traditionally been very difficult for advisers to work estate planning into their day-to-day efforts, especially since rising estate tax exemptions over the past 20 years have reduced the need for life insurance to provide liquidity to pay estate taxes (which was the primary way advisers were historically compensated for their estate planning advice). While every client needs to at least put the basic estate planning documents in place to ensure that their assets go where they want the assets to go, advisers have struggled to add value and get compensated in a space where they are not the ones paid to draft those documents.

There have been a few platforms to pop up in recent years to try and solve this problem for advisers, notably Yourefolio, Helios and Vanilla. They have all been getting various levels of traction over the years, but in August Vanilla announced a whopping $11.6 million Series A round, suggesting that Steve Lockshin may have cracked the code with Vanilla, leveraging his experience as an adviser building AdvicePeriod. The fintech entrepreneur sold Fortigent to LPL more than a decade ago and invested in some of the hottest fintech companies in the space, such as Quovo and Betterment.

Not just another ho-hum fundraising, this round was also led by Venrock, which seems to be developing quite an appetite for the adviser technology space (which is encouraging more generally around opportunities for AdviserTech entrepreneurs to raise capital). Joining Venrock in the round was William McNabb III, former CEO of Vanguard, who notably joined Altruist's latest round of financing and board of directors. Last, but certainly not least, Michael Jordan — the Michael Jordan — has joined this round of financing as well. Perhaps he has personally experienced the pain of trying to work with estate planning and financial advice together as a client of Lockshin’s, and believes in Lockshin’s vision of how it can be improved for all?

At its core, Vanilla provides estate planning software that helps advisers map out their clients’ current estate plans — from their potential estate tax exposure to the flowcharts of which assets will flow where — along with a dashboard to track the current estate planning status of all clients in the firm, with a particular focus on ultra-high-net-worth clients in a soon-to-launch Vanilla Ultra offering.

From there, as clients need estate planning updates (or their documents for the first time), Vanilla brings in attorneys to help draft those documents for the adviser’s clients, similar to Helios — a kind of higher-end “LegalZoom for advisers,” with a deeper level of adviser-specific technology and adviser-level service support (recognizing that clients who work with advisers don’t want a do-it-yourself solution but an adviser-supported one). This is a huge efficiency and value-add for advisory firms working with more affluent clients who have more complex estates, as advisers continue to look for ways to add value to fight off fee compression. Estate planning oversight and advice is a great value-add for that traditional 1% AUM fee for clients with complex estates, and certainly contributes to a more holistic view of the financial plan itself.

“Show your clients that you care about more than their money” is the hook that Vanilla uses in its pitch to advisers. It’s a good one because the issues that arise when a client is thinking about their estate go far deeper than just portfolio returns and asset allocation. Estate planning brings the deep questions to the surface that allow an adviser to create true bonds with not only their clients but potentially next-generation heirs (as the adviser who’s involved in the estate planning process gains a near-perfect view into the path of that client’s wealth for generations, at least and especially for the most affluent clients, who represent some of the biggest opportunities for advisers). And by leveraging tools like Vanilla to provide a clear view/report of a client’s estate, the adviser can see opportunities for tax optimization and personalization, and be armed with relevant information to engage the second and third generation of those estates.

As advisers lean further and further into planning being their ultimate value, firms will continue to become more focused not just on technology but on additional services for clients (where software enables it to happen efficiently). Outsourced insurance planning desk? Check. Outsourced tax return preparation? And now outsourced estate planning document creation? Check. When robo-advisers first showed up, the fear was that they would cause compression of the traditional 1% AUM fee; instead, though, fees have remained robust, but advisory firms are increasingly feeling the pressure to show more and more value beyond the portfolio alone — which Vanilla appears well-positioned to address, especially for the most affluent clients who today are showing the most fee scrutiny.

“I’m traveling out of the country and was injured in an accident. The hospital does not accept U.S. insurance, and I’m not carrying very much cash. I’m sorry this request is coming in late on a Friday afternoon, and I won’t be reachable because the hospital doesn’t allow incoming calls to patients, but I need $17,000 wired to the following bank ASAP so I can be discharged today and catch my return flight back to the U.S. this weekend.”

It’s the request that no advisory firm wants to see come in from one of its biggest clients. Late on a Friday afternoon, many team members may have already departed, which means there may not be a manager on-site to help review the situation. The client’s situation sounds dire, and no operations associate wants to put their job on the line by failing to fulfill a high-stakes request by a key client in a tough situation. Except it turns out that the client is just fine. The request came in from a hacker trying to impersonate the client, and by the time anyone realizes what happened when they come in on Monday morning, the money is almost certainly gone for good.

Over the past decade, advisory firms have increasingly been targeted as an access point for hackers and frauds trying to steal money from their affluent clients. We have all heard the horror story about a hacker impersonating an adviser’s client, requesting fraudulent payment or transfer. The levels of sophistication on these attacks are higher than ever — from spoofing client email addresses, using fake addresses that look almost identical to the client’s, or in some cases actually hacking the client’s email and sending a message that really is from the client’s email address and is even written in their style (because it’s copied from a prior transfer request in their Sent folder).

Notably, though, it’s not only advisory firms that are potentially on the hook in such situations. RIA custodians themselves can be deemed liable for complying with a request that turns out to be fraudulent and not putting sufficient checks and balances in place to prevent the crime from occurring. That has put RIA custodians in an increasingly difficult spot, as often they are only acting upon the request of advisers using their platform — which makes it more difficult for the custodian to verify the request — and in some cases, it’s the adviser’s own lack of cybersecurity that ends up creating a liability exposure for the RIA custodian.

In that context, it’s perhaps not surprising that in September, Fidelity announced a new partnership with Armorblox to provide cybersecurity services to any advisory firm that works with Fidelity Institutional. Armorblox is specifically focused on email security, and alerts financial advisers about fraudulent email activity, as well as automatically preventing phishing attempts and other email-based attacks.

Why Armorblox though? Hasn’t email security been around for 20 years or so? According to Fidelity, it takes a lot more time and effort for the operations teams at individual advisory firms to figure out their email cybersecurity than it should. Armorblox not only reportedly does the job well, but supposedly it reduces the amount of time that a team needs to spend on email protection. More security for advisory firms, and less time for firms not inexperienced in cybersecurity to get it right.

More broadly, though, the Fidelity-Armorblox deal opens the door for an interesting potential trend. Will custodians begin to supply more tech and funding to eliminate cybersecurity threats for their advisers’ clients? Given not only their own liability exposure (the FBI estimates there were $2.1 billion in reported losses from these types of attacks!), but also that Fidelity’s Investor Insights study shows that 58% of clients said they would switch advisers if there were reports of security breaches involving clients at the firm (resulting in a lost client for both the advisory firm and the RIA custodian that is blamed as the holder of their assets).

Let’s face it, most advisers know that this stuff is important, but they struggle to find the time to research all the tools and implement one in their practice. A curated solution from a big RIA custodian is arguably a tremendous value-add, and in turn, it greatly reduces the custodian’s potential liability (in addition to being good for advisory firms to get their cybersecurity squared away). Simply put, RIA custodians are finding that providing cybersecurity tech to their institutional advisory firm clients likely costs a whole lot less than the damages from the lawsuits if they’re found liable, which means as long as cybercrime continues to rise, RIA custodians providing cybersecurity support is only likely to continue as well?

Email overwhelm is real these days, and virtually everyone struggles with how much our email inboxes are stuffed with marketing material from every type of company (often leaving us scratching our heads about how we even got onto so many lists in the first place). The challenge of email marketing spam is so widespread that many people end out creating entirely separate email addresses just for that purpose, making it easier to screen out the marketing noise altogether. That in turn is leading marketers to try to find new channels to stay in front of those they’re trying to market to.

As email becomes increasingly saturated as a marketing channel, the new frontier has become text messages, as most people are never ever more than 6 feet away from their smartphone devices (and those text message notifications) at any point during their waking hours. That means text message marketing has more opportunity to reach prospects than increasingly filtered email.

To capitalize on the trend, Snappy Kraken is aiming to help advisers stand apart from the email marketing noise with a new product called Convos, which allows advisers to do text-message-based marketing.

Notably though, with Convos, advisers will generally send preconstructed text messages (either single messages, or multiple messages over time), from pre-generated conversation starters to specific educational content to prompts for setting up a meeting. In other words, advisers don’t simply type out their own text messages, but select from Convos’ prebuilt text message marketing campaigns. That takes the pressure off advisers to figure out what to send as a text message to engage — instead allowing Snappy Kraken to optimize campaigns that any adviser can apply — and in turn also allows all the marketing text messages in Snappy Kraken’s Convos library to be Finra-preapproved for compliance purposes (and then, with integrations to popular CRMs and MyRepChat, can be recorded and archived as well).

Understandably, there is some apprehension from the market about whether or not consumers are really ready to open up our SMS or iMessage inboxes to marketing. If email has already been co-opted, will prospects willingly opt in to another medium for that? But the reality is that the text-message-based marketing seal has already been broken. I receive text messages from businesses on a regular basis, and I’m sure the rest of you do as well. Which means at this point, advisers who ignore the channel are at risk of being left behind if more marketing shifts there over time. And at least Snappy Kraken’s prebuilt campaigns have the potential to implement text-message-based marketing more tactfully than some advisers might do on their own without marketing experience in the channel.

After all, when push comes to shove, marketing is all about relevance, trust and attention. We all may receive emails or text messages, but that doesn’t mean we convert. It has to be good content, likely from a trusted source, in order for us to consume it. If Snappy Kraken’s Convos messages can give advisers the right messages that enhance relevance, trust and attention, then there is arguably still ample room for advisers to turn text-message marketing from just another channel of marketing overwhelm for prospects into a genuine plus for connecting with new prospects.

New Product Watch: MONEYMAP.IO AIMS TO INTEGRATE (SCALABLE) HUMAN ADVICE BACK INTO ROBO FINTECH PLATFORMS

When robo-advisers first launched a decade ago, the vision was that technology could automate what financial advisers did — from opening investment accounts to determining appropriate investment allocations and then implementing the subsequent investment trades — and in the process, win consumers by pricing at barely one-fourth of what human advisers charged for the same services.

Yet in the decade since, not only have robo-advisers failed to win much market share from human financial advisers (as Betterment and Wealthfront combined have still not quite crossed $50 billion of AUM, in an industry where total US investible assets are more than $42 trillion), nor have they shown any adverse impact on advisory fees (in fact more financial advisers are raising financial planning fees than cutting them), but instead robo firms have increasingly been adding human financial advisers to their technology offerings.

The end result is that even the largest robos today are platforms offering human advisers with CFP certifications to augment their technology-automated advice, from Vanguard’s Personal Advisor Services (now approaching 1,000 human CFP professionals), to Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolio’s Premium, and even Betterment’s own Premium offering. Not only are platforms offering human financial advice to augment their technology solutions growing faster and commanding more new clients and assets, but offering human financial advice has also effectively become an upsell for those platforms — a higher-priced offering for a higher tier of (more human) service.

The caveat, though, is that human financial advisers are much more challenging to scalethan stand-alone robo technology. From adviser recruiting to retention, training to quality control, scaling a service business is fundamentally different from scaling a technology solution with respect to the time, cost and other required resources. In practice, relatively few fintech firms have managed to layer in a human adviser solution on top of their technology platform, despite the consumer demand.

But now, a new platform — Moneymap.io — is looking to change this by building a platform that will make it easier for fintech firms to roll out their own white-labeled human advice offering. In essence, Moneymap has created a technology platform that makes it easy for consumers to set a basic financial goal — for instance, establishing an emergency savings account, tackling a credit card problem, creating a will or rolling over an old 401(k) plan — and then work with a CFP professional through the Moneymap platform to give advice about what to do, help the client build confidence that they can achieve the goal, and serve as an accountability partner to help ensure they follow through and actually act. (Moneymap designed the engagement system with Dan Ariely, of “Predictably Irrational” behavioral finance fame.) In turn, for consumers with more complex advice needs, MoneyMap can partner with outside CFP professionals — in other words, serving as a new form of adviser-referral channel providing leads to affiliated firms.

Of course, the reality is that fintech platforms could create such technology and referral networks themselves. But when most fintech firms are funded by venture capital or private equity — and their investors demand faster growth rates and scalability than what it takes to build a quality human adviser infrastructure — Moneymap is well positioned to plug into existing fintech firms that want to expand into human advice, but don’t actually want to build it themselves. Moneymap was architected with an API structure that allows it to be easily integrated into other existing fintech firms that want to white-label Moneymap’s solution.

It remains to be seen whether more fintech firms really will try to roll out human advice services to capture the additional pricing power of what consumers are willing to pay for human advice and a human accountability partner. But to the extent that “speed of deployment and ability to scale rapidly” seem to have been the biggest blocking point historically, Moneymap seems well positioned to expand the human financial advice ecosystem, allowing fintech firms to revenue-share on Moneymap’s advice services and the fees it earns to refer more affluent clients to related advisers (not to mention deepening their engagement with their users). And in the process, create both new job opportunities for CFP professionals, and a potential new lead generation channel for independent advisory firms?

In the meantime, we’ve updated the latest version of our Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map with several new companies, including highlights of the “Category Newcomers” in each area to highlight new fintech innovation!

So what do you think? Will advisers shift toward direct indexing platforms as a way to build more customized, personalized and differentiated portfolios for their clients? Can Vanilla gain traction with financial advisers offering estate planning as the next big value-add for affluent clients? Will enterprises increasingly adopt fee-for-service financial planning if AdvicePay makes it easier to automate payments and compliance? And will MoneyMap be able to convince fintech firms of the benefits of bringing in human financial advisers to a historically pure fintech solution?

Disclosure: Michael Kitces is a co-founder of AdvicePay, which was mentioned in this column.

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter at @MichaelKitces.

You can connect with Kyle Van Pelt via LinkedIn or follow him on Twitter at @KyleVanPelt.

The deal will see the global alts giant snap up the fintech firm, which has struggled to gain traction among advisors over the years, for up to $200 million

Elsewhere, Osaic extended its reach in Knoxville with a former TrustFirst team, while Raymond James scored another win in the war for Commonwealth advisors.

Meanwhile, EP Wealth extended its Southwestern presence with a $370 million women-led firm in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The recently enacted OBBBA makes lower tax rates "permanent," though other provisions could still make earlier Roth conversions appealing under the right conditions.

Americans with life insurance coverage are far more likely to feel assured of their loved ones' future, though myths and misconceptions still hold many back from getting coverage.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.