When things are going badly in the market, a household and a hedge fund create the same sort of market risk dynamic: a downward leverage- and liquidity-driven cascade. Hedge funds are acutely aware of how leverage and low liquidity can pull them into deep waters. Advisers need to keep in mind how this risk dynamic can play out within households as they navigate their clients through the current market turmoil.

The dynamic comes from the volatile combination of leverage coupled with low liquidity. If things go downhill, being highly leveraged means you have to sell, and when there’s a flood of selling, liquidity dries up and you end up chasing the market. The result is a downward cascade.

It can get worse because as liquidity dries up in one market, those who have to sell turn to other markets, creating contagion. This can be pretty perverse — sometimes the markets that are liquid, solid and just sitting around minding their own business are the ones that get hit. Because when you can’t sell what you want to sell, you sell what you can sell. And that’s the stuff that's the most liquid.

So when this leverage-liquidity dynamic plays out, you see violent drops in prices and contagion to other markets that seem to have no relationship. Actually, the operational relationship is that investors hold both of them in size.

The prominent domain for leverage is hedge funds, which is why they can generally be well-behaved, but crash and burn in times of stress. When it’s hedge funds behind the leverage-liquidity dynamic, it’s more or less a flash in the pan because in the grand scheme of things, they're not so big relative to the market. It’s like what someone once said to me when I had food poisoning: “It’s violent but benign.”

What’s not benign is when a giant swath of the market gets caught up in the dynamic. Want a really big swath? Try households.

There’s a lot of focus on hedge funds and other institutional investors when this sort of dynamic is unleashed — not so much on households. Individuals get little to no guidance from mainstream sources. That’s why the adviser-client relationship is so critical, and why advisers need to have the tools to assess where their client sits within the household matrix of leverage and liquidity.

Households might not be a fixture on the nightly business news, yet they control a huge proportion of liquid assets. When they get embroiled in a leverage-liquidity cascade, it’s no flash in the pan; it’s like a supertanker changing course. It will unfold slowly, because where a hedge fund might face a margin call, households don’t. They see their high debt, see higher costs, see lower asset prices, and start to adjust gradually, with different households reacting at different levels of market stress. Looking at the aggregate, these adjustments can be harrowing.

This is all a large preamble to the point (my journalist spouse would say, “You’re burying the lede”): By and large, households currently are levered, concentrated and not very liquid. Here are charts with some of the data I use in risk models to make that point.

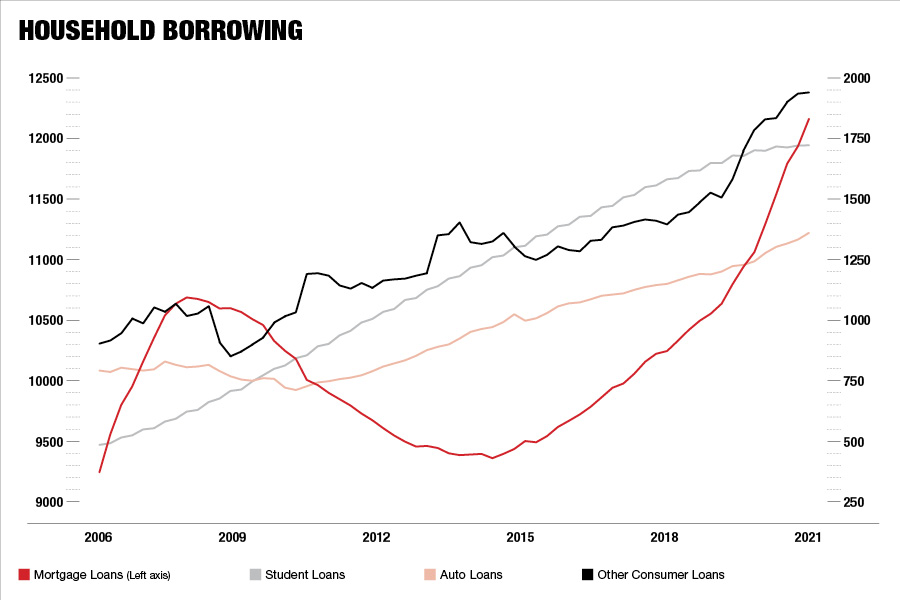

Leverage. The leverage for households isn’t in the market; it's in debt. Debt has been rising like there's no tomorrow, and it's rising as costs are rising as well. This doesn’t lead directly to forced liquidations in the market. But it has the same effect.

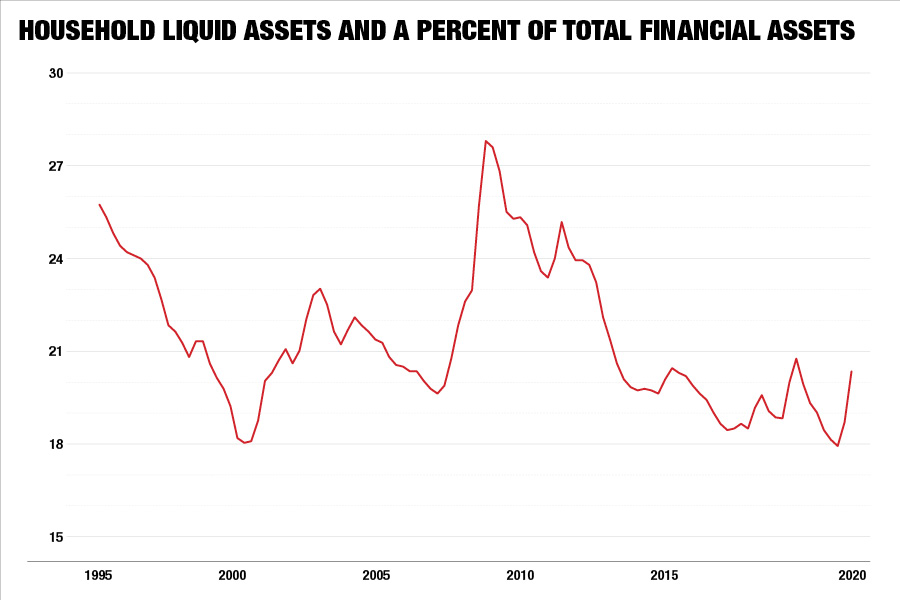

Liquidity. The percentage of financial assets that are liquid is near the lowest level in the last 25 years, with a little pop up over the past few months. Tellingly, the other dips were in the run-ups to 2000 and 2007.

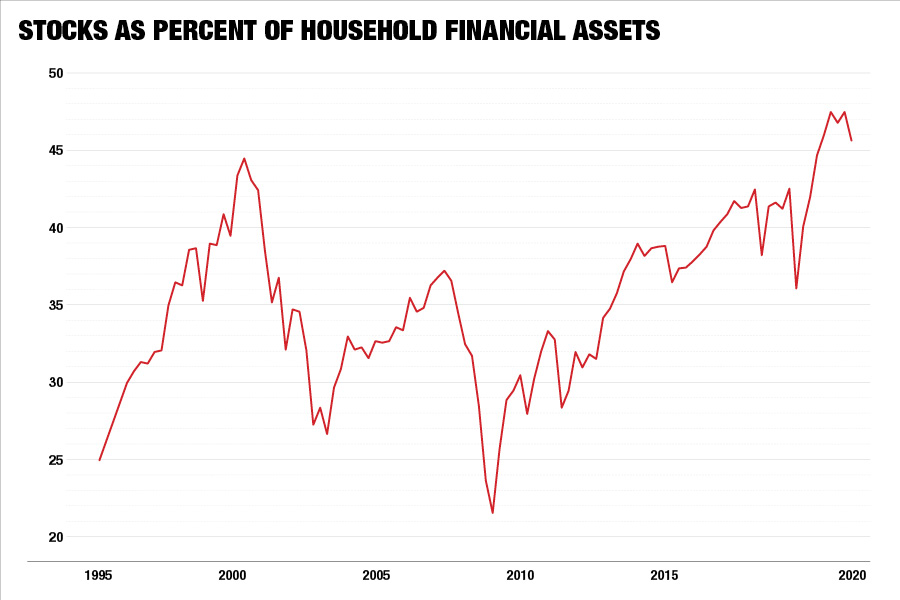

Concentration. The percentage of household liquid assets in equities is at an all-time high. This chart has numbers ending a month ago, so the portion is probably on the way down as the market drops, but it's still at an all-time high.

Given this, there are two points of action: First, find out where your clients sit relative to the borrowing, liquidity and concentration shown in these charts, and make adjustments accordingly. Second, rehearse with your clients the implications of this dynamic for their portfolio even if they are not directly in the path. That is, talk about what might happen and what the plan is if households start a cascade.

Rick Bookstaber is co-founder and head of risk at Fabric. He previously held chief risk officer roles at Morgan Stanley, Salomon Brothers, Bridgewater Associates and the University of California Regents, and served at the Treasury in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. He’s the author of “The End of Theory” (Princeton, 2017) and “A Demon of Our Own Design.”

"This shouldn’t be hard to ban, but neither party will do it. So offensive to the people they serve," RIA titan Peter Mallouk said in a post that referenced Nancy Pelosi's reported stock gains.

Elsewhere, Sanctuary Wealth recently attracted a $225 million team from Edward Jones in Colorado.

The giant hybrid RIA is elevating its appeal to advisors with a curated suite of alternative investment models, offering exposure to private equity, private credit, and real estate.

The $40 billion RIA firm's latest West Coast deal brings a veteran with over 25 years of experience to its legacy division for succession-focused advisors.

Invictus fund managers allegedly kept $10 million in plan assets after removal, setting off a legal fight that raises red flags for wealth firms.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.