For more than two decades, inflation hawks have warned incorrectly that an inflationary outbreak is “just around the corner.” Haunted by memories of the double-digit inflation of the late 1970s, they repeatedly suggest that the US economy is poised for runaway inflation and that dramatic action needs to be taken immediately, before we see our trust in the future eroded and the very pillars of capitalism undercut.

The latest round of fiscal stimulus on top of ultra-loose monetary conditions has brought inflation hawks back into the spotlight. Former Treasury secretary Larry Summers and former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard have cautioned that the additional stimulus package recently passed by Congress will overheat the US economy and ignite inflationary pressure not seen in a generation. With the yield on the 10-year Treasury climbing above 1.6%, many wonder if runaway inflation is around the corner, and investors are scouring their portfolios to see whether they’re prepared.

Some modest level of inflation is a sign of a healthy, growing economy. It’s likely that we’ll experience price increases in excess of this normal trend as the economy comes out of lockdown. Investors should understand that not all inflation scenarios are the same. Think about the possibilities in three broad scenarios:

The first two outcomes appear to align with the Fed’s expectations for the economy. After the January Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, Fed chair Jerome Powell stressed that there were no plans to raise interest rates to head off inflation. Instead, the Fed intends to wait to see actual price pressure in the data before tightening. That means policymakers won’t be preemptive or react to short-term price spikes; instead, they’ll b wait for evidence of sustained upward price pressure. That dovish stance was reiterated after the March FOMC meeting. The Fed’s accommodative position coupled with massive fiscal stimulus concerns inflation hawks. They understand it can be painful to eradicate inflation once it takes hold. (They might point to September 1981 and its 15% 10-year Treasury yield as a cautionary tale.)

Determining which economic scenario will play out is an exercise in estimating slack in the economy. Under all scenarios, investors should expect to see headline inflation tick up in the short run as the economy reopens. What separates the third scenario (inflation returns) from the other two is that in it, prices continue to increase beyond the short term. That type of sustained long-term price increase will occur only if the economy is producing above its long-term potential. The output gap is what economists use to measure the difference between actual and potential GDP.

A positive output gap means the economy is running above full capacity: Demand is high and businesses and workers operate above their efficient capacity. A negative output gap occurs when output is less than the economy could produce at full capacity. This means there’s spare capacity, or slack, in the economy as a result of weak demand. To understand whether a return to 1970s-type inflation is in our future, we need to focus on the output gap.

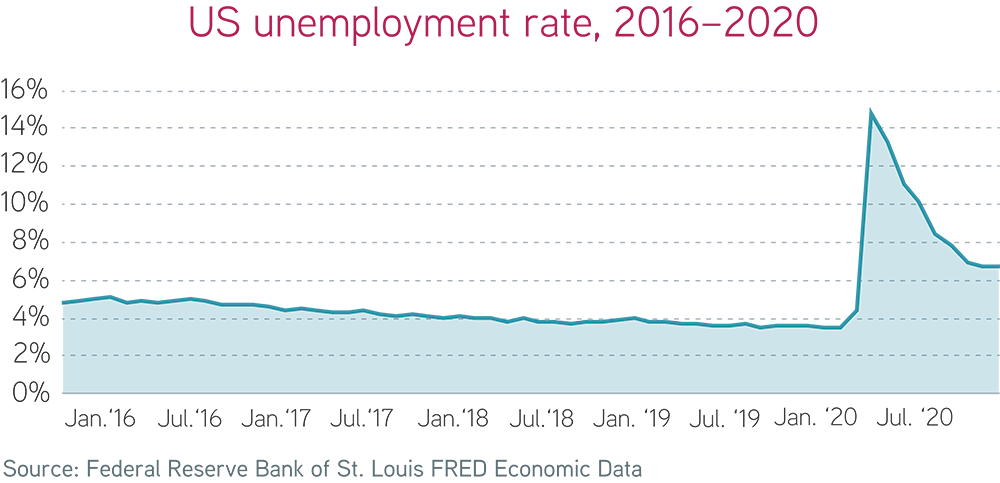

Unfortunately, the economy’s potential isn’t directly observable. At best, it’s a theoretical condition economists estimate with a high degree of uncertainty. A proxy many utilize for potential GDP is the health of the labor market. The argument is that the economy cannot be overheating with rising wages when vast numbers of people remain on the sideline unemployed. The current unemployment rate is nearly double the levels we experienced in the months leading up to the pandemic onset.

The US economy has 10 million fewer jobs today than in the months before the pandemic. The pandemic has caused the largest 12-month decline in labor force participation since 1948. On February 10, Fed chair Powell suggested that the real unemployment rate could be closer to 10%, a level likely to preclude sustained inflationary pressure. That same month, the Congressional Budget Office forecast that unemployment wouldn’t reach its prepandemic level until 2024.

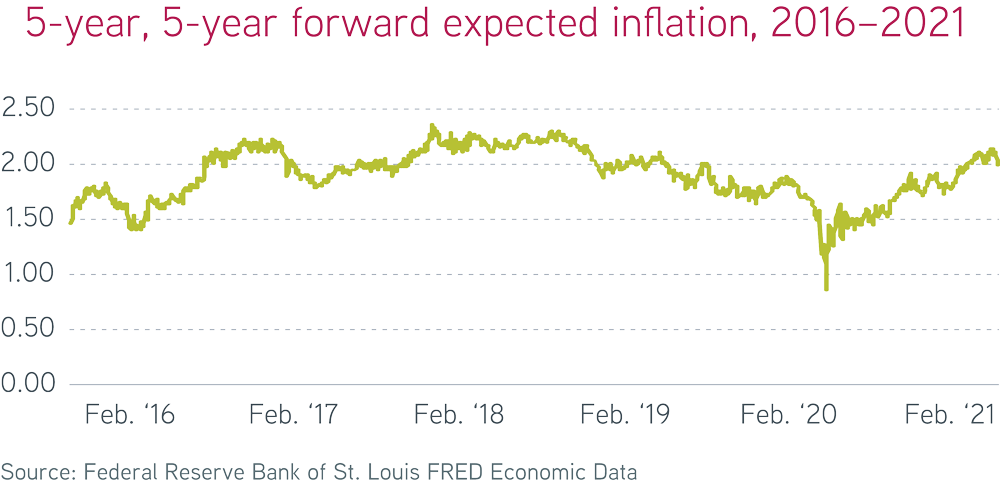

We can also use one of the Fed’s forward indicators to see how the market interprets the gap and subsequent risk of long-term inflation. The Fed strives to keep inflation expectations anchored near 2%. If that expectation is widely held, then short-term blips above or below 2% will represent noise around the long-term signal. Former Fed chair Ben Bernanke outlined the importance of anchoring long-term inflation expectations in a 2007 speech.

The five-year, five-year forward inflation expectation measures the average expected inflation over a five-year period that begins five years from today. This longer-term gauge removes the influence of short-term blips and highlights where inflation expectations are anchored. It’s not a perfect indicator, particularly when the Fed is involved in quantitative easing, but it does provide insight into market expectations. The market isn’t currently pricing in a long-term rise in inflation. The Fed has successfully anchored expectations around a 2% target.

Some above-trend inflation is to be expected as the economy begins to open up more broadly. It can be argued that a modest jump in inflation should be viewed as a positive sign, indicating the economy’s return to normal. Long-term price pressures leading to double-digit inflation are possible but not likely, given the slack that currently exists in the economy.

Elsewhere in Utah, Raymond James also welcomed another experienced advisor from D.A. Davidson.

A federal appeals court says UBS can’t force arbitration in a trustee lawsuit over alleged fiduciary breaches involving millions in charitable assets.

NorthRock Partners' second deal of 2025 expands its Bay Area presence with a planning practice for tech professionals, entrepreneurs, and business owners.

Rather than big projects and ambitious revamps, a few small but consequential tweaks could make all the difference while still leaving time for well-deserved days off.

Hadley, whose time at Goldman included working with newly appointed CEO Larry Restieri, will lead the firm's efforts at advisor engagement, growth initiatives, and practice management support.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.