Over the past year, advisors may have “recession-proofed” their clients’ portfolios.

For good reason: Depending on whom you ask, the markets could already have priced in a recession. About two-thirds of economists think one is coming in 2023, according to a World Economic Forum survey. And despite a rosy recent jobs report, the Federal Reserve projects unemployment will inch up this year, to 4.2%. While that’s low by historical standards, it still suggests more than 8 million looming job losses.

If the forecast bears out, some of those job losses will include advisors’ clients, who from their work with a professional should at least have an emergency plan and a portfolio attuned to their risk tolerance. But where does that leave advisors themselves?

If history is any guide, there’s good news.

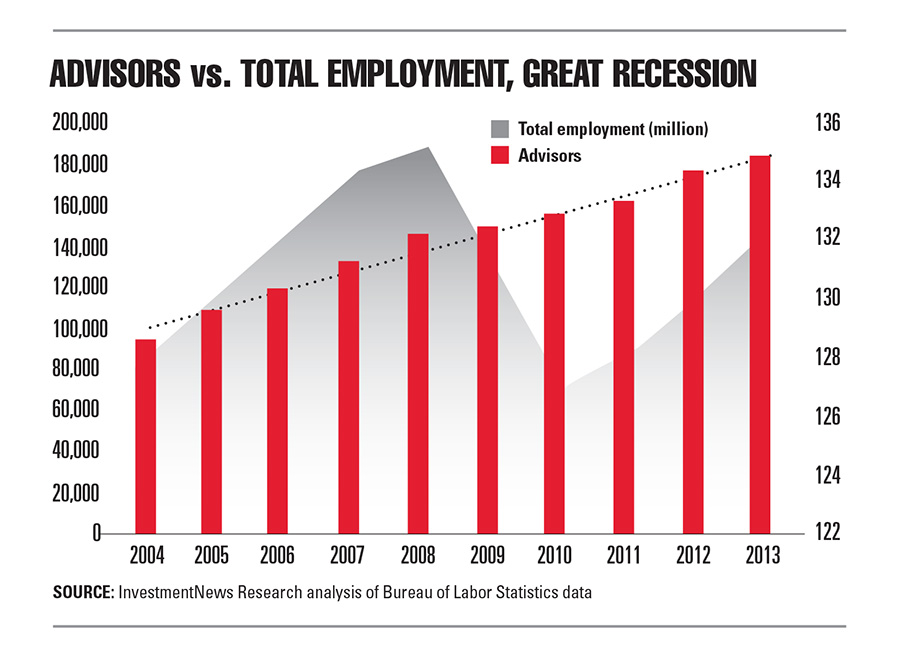

Financial advisors were among the most recession-proof occupations during the Great Recession, according to an InvestmentNews Research analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The analysis focused on high-earning professions where hiring wasn’t countercyclical (i.e., showing temporary growth occurring only during the recession). From 2007 to 2010, the peak years of overall job loss, the advisory profession gained about 23,000 people, making it the fifth most secure profession in the analysis.

While many of the safest jobs during the last prolonged recession were concentrated in common fields like health care and engineering, financial advice was a refuge within its sector. Advisor employment rose 17.3% during the peak job loss years even amid a 9.3% decline in total finance and insurance sector employment. Occupations like loan officers, accountants and credit analysts were among the hardest hit overall.

Part of the rise in advisor employment in this period could reflect the prevalence of career-changers in the field. The data are limited on this, but job losses in other financial occupations could have led those professionals to pivot into the growing field of advice. Yet that still doesn’t explain why the market for advice supported such an influx of professionals during a down period.

Academics Yuanshan Cheng, Charlene M. Kalenkoski and Philip Gibson later examined the Great Recession’s impact on the hiring and firing of advisors in the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, hypothesizing consumers would be driven to and from advisors primarily by loss of wealth or income.

Instead, they found that although an increase in income had a significant impact on whether consumers hired advisors, losses did not significantly raise the likelihood of an existing client firing their advisor. Demographics like education, which they used as a proxy for an understanding of the market, were more important.

“Our results show that clients do not fire their financial advisor because they experience a decline in net worth during recessionary periods,” they wrote, but “demographics and psychological characteristics of clients have a greater impact on the advisor-client relationship.”

In other words, advisors can see upside from the portions of the economy still doing well during a recession, without as much downside from current clients faring worse. More recent research lends the idea credence: In a consumer survey conducted last year by InvestmentNews, only 17% of respondents working with an advisor said they would be very likely to fire them over a decline in their portfolio.

Of course, every downturn is different. Case in point: This analysis ignored the middle of 2020, which despite meeting the technical definition of a recession offers little in terms of precedent. Even a recession that looked more like 2009 would be shaped by new variables.

For advisors, perhaps the biggest variable is the 15 years of industry technology that has arrived since.

Yet there’s little reason to believe the industry has the technology on hand to significantly reduce the need for human advisors short term. Surveys of technology decision-makers at firms have shown spending rising year after year, but mostly on client acquisition tools like CRMs, digital onboarding programs and marketing software.

For all the technology bringing in new clients, it’s not clear the economics of serving them have changed much. From 2018 to 2021 (the latest year available), the InvestmentNews Advisor Benchmarking Study tracked a 51% increase in average firm spending on technology. Over the same period, the average number of clients served by advisors fell to 73 from 74. Client relationships grew more lucrative, and tech likely played a role, but it didn’t change the human capacity required to serve clients.

That’s not to say evolving trends like the rise of DIY investing or emerging technology like artificial intelligence won’t pose longer-term threats to the profession. But they are likely a longer way off than the next recession.

So advisors can probably continue to assuage their clients’ recession fears without sweating their own jobs too much. Still, a little recession-proofing never hurts.

[More: Most recession-proof jobs]

[More: Least recession-proof jobs]

Rajesh Markan earlier this year pleaded guilty to one count of criminal fraud related to his sale of fake investments to 10 clients totaling $2.9 million.

From building trust to steering through emotions and responding to client challenges, new advisors need human skills to shape the future of the advice industry.

"The outcome is correct, but it's disappointing that FINRA had ample opportunity to investigate the merits of clients' allegations in these claims, including the testimony in the three investor arbitrations with hearings," Jeff Erez, a plaintiff's attorney representing a large portion of the Stifel clients, said.

Chair also praised the passage of stablecoin legislation this week.

Maridea Wealth Management's deal in Chicago, Illinois is its first after securing a strategic investment in April.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.