The pandemic pushed millions of older Americans out of the labor force. It should have spawned a surge in applications for Social Security benefits — but it hasn’t. Perhaps because they aren’t retired. The disconnect has economists wondering how many of these baby boomers might come back to the workforce — a key question when job openings have remained near record levels for months now.

Here’s a look at the data and the debate it has spurred:

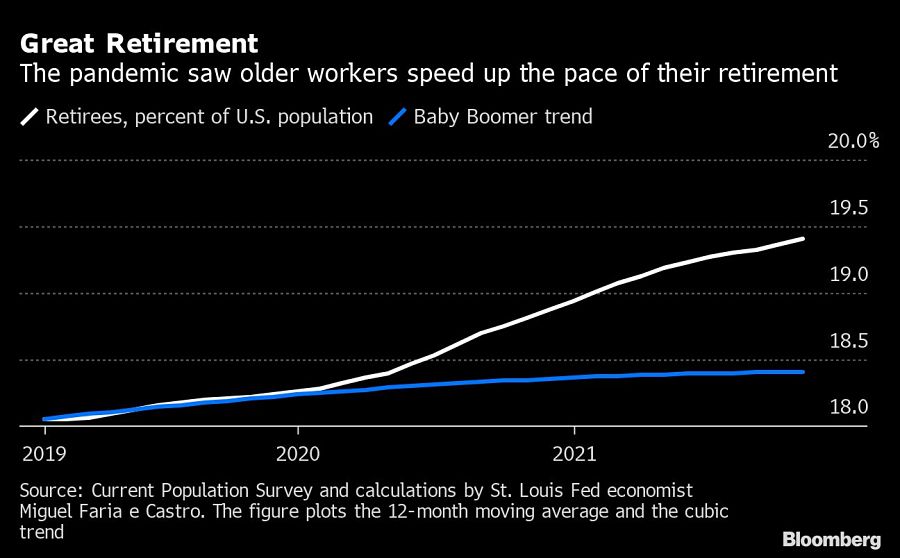

The retired share of the population is now substantially higher than before Covid-19, according to a Federal Reserve analysis. About 2.6 million older workers retired above ordinary trends since the start of the pandemic two years ago, based on estimates by Miguel Faria e Castro, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Under the U.S. federal retirement program, eligible workers receive a percentage of their pre-retirement income in monthly payments from the government. Workers can start receiving Social Security payments at age 62, with full benefits coming at age 66 or 67 depending on their date of birth.

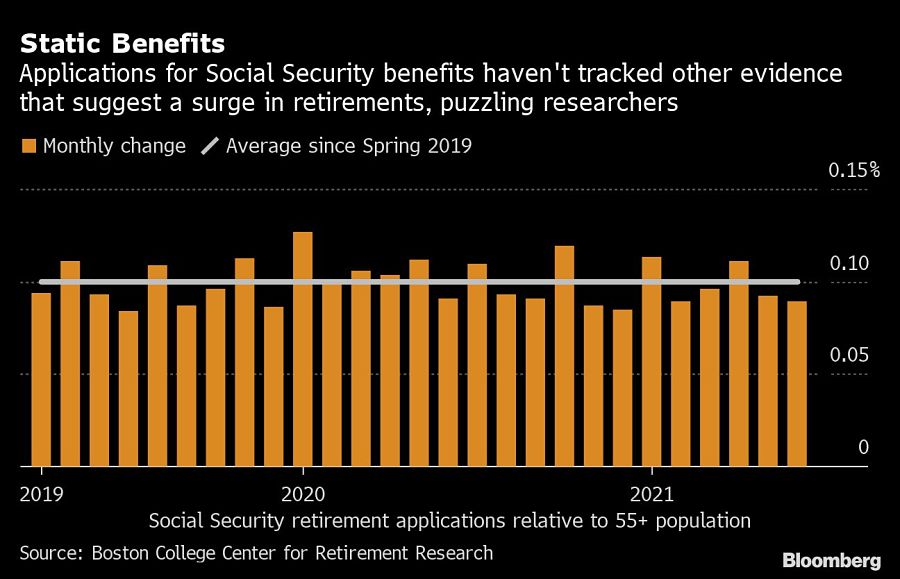

Despite the surge in baby boomers saying in surveys they retired, applications for Social Security benefits have been fairly flat, based on calculations by the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. Around 0.1% of the U.S. population 55 and older have applied each month, which is consistent with what was happening before the pandemic.

The lack of Social Security filings is a bit of a mystery for Laura Quinby, a senior research economist at the Center for Retirement Research. Older Americans often feel the need to apply for benefits in person, so the closure of the Social Security Administration's local offices during the pandemic might have dissuaded some from applying.

Others might be waiting to reach their late 60s to be eligible for full benefits, Quinby said. Thanks to the Covid-era boom in stock and real estate values, individuals who own assets and have savings can afford to delay applying.

The surge in assets made this an “opportune time for some workers to step out of the labor force and stay out of the labor force,” said Lowell R. Ricketts, data scientist for the Institute for Economic Equity at the St. Louis Fed.

“But we’re still expecting a steady, steady trend that some might want to come back,” he said, especially with the advent of remote and hybrid work, which may lure seniors back to the job market.

Unlike in other developed countries, retirement isn’t necessarily a permanent shift in the U.S. Before Covid, it wasn’t uncommon for Americans to “un-retire,” because of financial hardship or personal choice. It’s too early to tell whether the pandemic has changed that dynamic permanently or not.

The Social Security Administration’s Office of the Chief Actuary suggested older people may have “retired” from one job and continued working in another. That would explain why they’re not applying for benefits.

And people under 62 wouldn’t qualify for Social Security anyway. Among them is Hope Cabot, 61, who left her teaching job in Roswell, Georgia, in December. The stress of caring for a mother and having to teach virtually pushed her to retire sooner than she anticipated. Cabot plans to work as a substitute teacher to stay busy and bring in some extra cash to help keep up with high inflation, she said.

“During the pandemic, it was crazy,” she said. “I was not planning on retiring until the end of this year or the end of next year.”

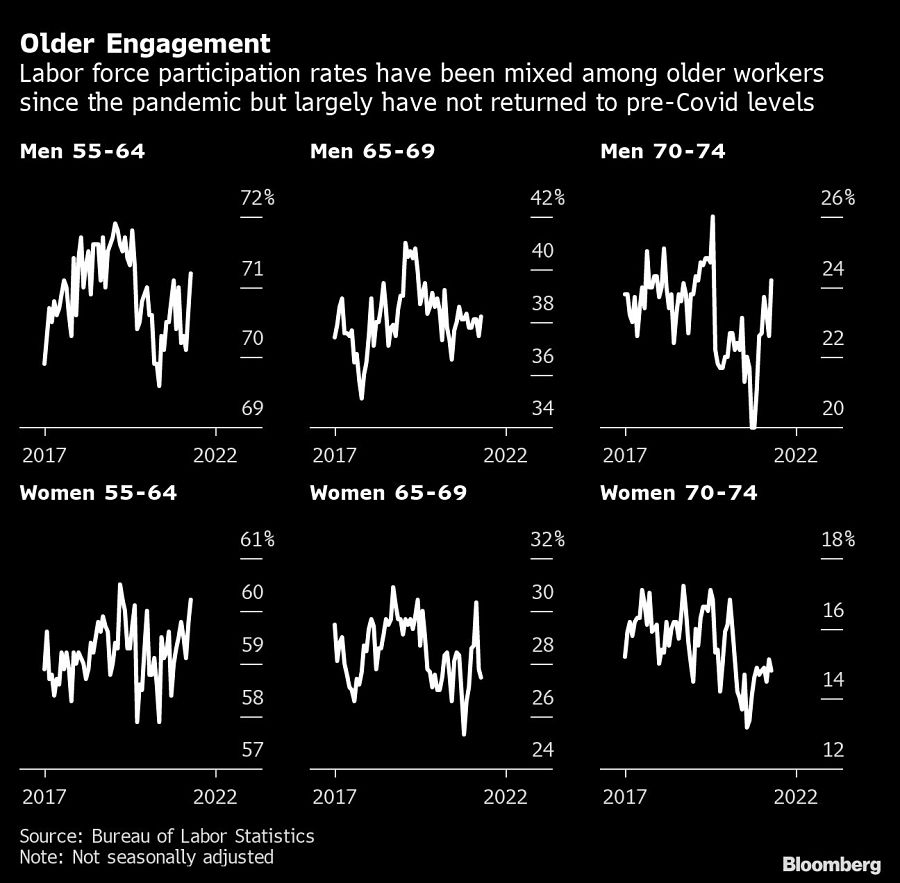

So far Bureau of Labor Statistics data on labor participation show that some baby boomers have come back, while many are remaining on the sidelines.

It’s possible that Covid-19 has led to a reckoning for a generation that reached retirement age when a global pandemic hit their age group disproportionally and threatened life as we knew it. It makes it even more difficult to predict if and when they might look for a job again.

“Just as is the case with younger workers who have seen opportunities to think differently about their lives, people in this demographic are thinking, ‘What do I really want to do with my life,’” said Doug Dickson, who chairs the Encore Boston Network, which helps older workers find a job or volunteer opportunities. “Are they really retired or are they just defaulting to that language because it’s the easiest way to characterize it?”

A new proposal could end the ban on promoting client reviews in states like California and Connecticut, giving state-registered advisors a level playing field with their SEC-registered peers.

Morningstar research data show improved retirement trajectories for self-directors and allocators placed in managed accounts.

Some in the industry say that more UBS financial advisors this year will be heading for the exits.

The Wall Street giant has blasted data middlemen as digital freeloaders, but tech firms and consumer advocates are pushing back.

Research reveals a 4% year-on-year increase in expenses that one in five Americans, including one-quarter of Gen Xers, say they have not planned for.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.