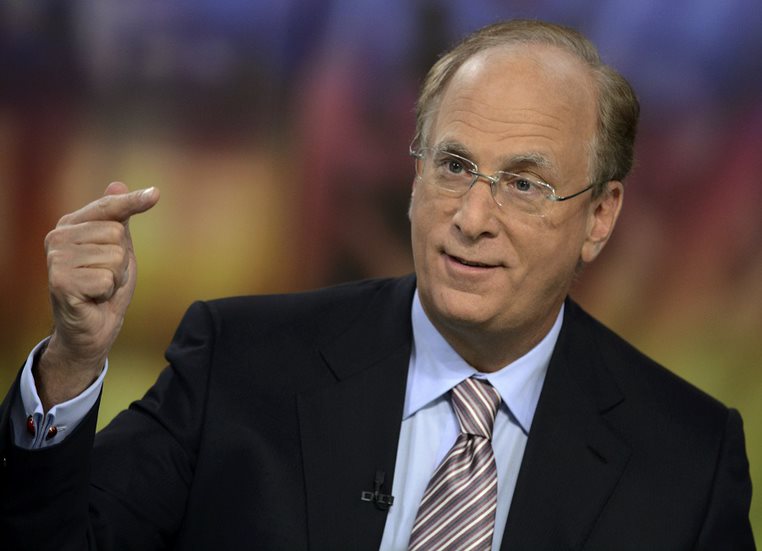

Larry Fink, CEO of the world’s largest asset manager, found himself on the back foot after a handful of conservative state officials called out his climate advocacy for what they see as political posturing. At the same time, liberals are condemning him and his 3,300-word letter to stakeholders as all talk and little action.

Fink will surely pass unscathed between Scylla and Charybdis. BlackRock’s $10 trillion in assets under management is ample body armor. But he may aspire to more than merely the kingdom of Wall Street, and through will, guile and resources, walk a fine line to bridge the great national political divide over the issues of environmental stewardship, social justice, and dutiful governance. The framework for this line peppers BlackRock’s proxy voting guidelines for U.S. securities.

The conservative right pegs Larry Fink and much of the Business Roundtable as anti-growth. Citing a new Texas law that restricts the state from doing business with firms that refuse to work with energy companies, Dan Patrick, the state's lieutenant governor, wrote, “If Wall Street turns their back on Texas and our thriving oil and gas industry, then Texas will not do business with Wall Street.” The state’s beef: Last spring, BlackRock won widespread notice by backing three dissident directors seeking election to ExxonMobil’s board who wanted to fight the oil giant’s reluctance to move into renewable energy.

Riley Moore, the Republican treasurer of West Virginia, announced that he would block the state from using BlackRock for banking transactions, as the firm’s net-zero goal would harm his state’s coal industry.

Yet BlackRock is not categorically anti-fossil fuel. “Keep in mind, if a foundation or an insurance company or a pension fund says, ‘I’m not going to own any hydrocarbons,’ well, somebody else is, so you’re not changing the world,” Fink told a forum last year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

On the opposite side of the political spectrum, Sen. Elizabeth Warren has declared that the Business Roundtable pledge of stakeholder centrism and ESG primacy championed by Fink was “weak and meaningless,” and “just a publicity stunt.” BlackRock’s former head of its sustainable investing group, whistleblower Tariq Fancy, accuses the firm of greenwashing. So-called ESG investing, Fancy argues, merely allows fund managers to charge higher fees for investment products that have “scant or little evidence of real-world impact that would not have otherwise occurred.”

ESG pledges can’t be empty promises and they can’t include hollow threats. And they can’t only focus on the environmental and social parts of the ESG equation. E and S won’t amount to much if they aren’t backed by better governance, for it is governance that makes the right things happen. It's through better governance that both conservatives and liberals can find the common ground to diffuse the social and environmental tensions. It's a fine line that can bear great weight.

First off, Fink needs to recast the conversation into the framework of governance. A debate over whether a glass is half empty or half full can turn on the general agreement that a glass is twice as big as necessary for the time being. A debate over stakeholder capitalism and whether it is “woke” or “corporate puffery” can turn over the general agreement that at the heart of dutiful governance is the obligation of every board to protect their firm’s reputation for the net benefit of all stakeholders.

Why reputation? It is the product of stakeholder expectations and is operationally specific in that it refers to what stakeholders expect a firm will do. That’s the source of value in stakeholder capitalism. Rather than reflecting “woke” trends, risk to reputation value was crowned as far back as 2005 as the “risk of risks.” Reputation can be politically loaded or indifferent, all depending on what a specific firm’s stakeholders expect —making it politically and ideologically agnostic.

Also, BlackRock has already made it clear that it expects its investee firms to have processes for reputation risk oversight and management in place.

In its 2021 proxy advisory guidelines, BlackRock began asking companies to demonstrate an understanding of key stakeholders and their interests. The broad sweeping charge for better governance sat alongside two narrowly defined goals for social justice and environmental stewardship, both of which could be reasonably deferred in the name of dutiful governance if the conditions were inconsistent with the interests of key stakeholders.

In its 2022 proxy advisory guidelines, Blackrock spelled out this governance charge in greater detail. “We believe that in order to deliver long-term value for shareholders, companies should also consider the interests of their key stakeholders … We expect companies to effectively oversee and mitigate these risks with appropriate due diligence processes and board oversight.” That seems like something on which stakeholders like Massachusetts Sen. Warren and Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick ought to be able to agree.

A company whose board oversees the responsible consideration of all key stakeholder interests and pursues a strategy designed to deliver long-term value for shareholders is exactly the kind of company all stakeholders can appreciate and value.

The organizational mechanics are not difficult, because reputation is commonly a task for general counsel, enterprise risk management is well worked out, and authenticating reputation insurance can be used as a tool for drowning out charges of greenwashing. Line walking is not hard when it's an institutionalized process, and most important, it reframes any board action from being “arbitrary and capricious” to “dutiful and thoughtful.” It also enables firms to respond to the evolutionary arc of the business environment.

Over a decade ago, environmental groups began to express concerns to banks over the financing of businesses engaged in the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels. Some banks chose to engage stakeholders on these topics, and this engagement over time and through business cycles, directly or indirectly, resulted in reduced financial exposure to certain energy companies. The driver of the evolution in exposures: reputation risk management, institutional risk appetites and liquidity protection. In short, good corporate governance.

It's unlikely that any outcome is going to make ideologues from the right and the left happy. But strong governance and reputation risk management processes will enable companies to make better informed decisions and anticipate and mitigate any reputational fallout that may occur. That fine line should make their key stakeholders happy and is readily navigable.

Nir Kossovsky is CEO of Steel City Re, which provides parametric reputation risk insurances and advisory services using a risk management framework informed by behavioral economics. Denise Williamee is Steel City Re’s vice president of corporate services.

Wealth managers highlight strategies for clients trying to retire before 65 without running out of money.

Shares of the online brokerage jumped as it reported a surge in trading, counting crypto transactions, though analysts remained largely unmoved.

President meets with ‘highly overrated globalist’ at the White House.

A new proposal could end the ban on promoting client reviews in states like California and Connecticut, giving state-registered advisors a level playing field with their SEC-registered peers.

Morningstar research data show improved retirement trajectories for self-directors and allocators placed in managed accounts.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.