From tossing spare change into a red Salvation Army bucket at Christmas to donating millions of dollars’ worth of appreciated stock into a donor-advised fund at the height of a tech boom, charitable giving never goes out of style.

It’s always fashionable to dig into one’s pockets to give to a worthy cause. And the deeper the digging, the better too.

That said, the ideal methods for giving to charity do change over time, with fluctuations in the market, the economy, and tax rules. Much like Ebenezer Scrooge himself, the best ways to maximize donations during Christmases present and future do evolve.

Before being haunted by a poor charitable choice from the past, there are things to be done – and not just at Christmas time.

One of the most effective giving strategies advisors are sharing with clients right now − and especially for clients with low-basis, highly appreciated, concentrated stock positions − is the charitable remainder trust (CRT).

As many tech founders, executives, and early-stage investors consider liquidity or exit events, they’re also seeking tax-efficient ways to support causes they care about. Mike Kurz, director of programs at the Investments & Wealth Institute and CEO of OverShare Advice and Planning, for one, sees CRTs as offering a triple benefit: an immediate capital gains deferral, a prospective charitable deduction, and a stable income stream back to the client – while ultimately benefiting a charity with a lump sum down the road.

“The alignment between financial efficiency and philanthropic intent is what makes it so compelling in today’s environment,” Kurz says.

Elsewhere, John Nersesian, head of advisor education at PIMCO, says clients are being increasingly receptive to using qualified charitable distributions (QCDs) to effect charitable giving and to satisfy their required minimum distributions (RMDs) while avoiding an increase in their taxable income. The concept is available to clients above the age of 70½ and is currently capped at $108,000 per year.

An emerging strategy that’s gaining traction, according to Kurz, involves leveraging Section 1202 of the Internal Revenue Code, which allows for the exclusion of up to 100 percent of capital gains on the sale of qualified small business stock (QSBS) held for more than five years. For clients facing a significant liquidity event such as a startup exit, he says this provision can dramatically reduce or eliminate federal capital gains taxes.

“Founders should be thinking today about how to get significant tax breaks with Section 1202 that would allow the owners to potentially avoid capital gains taxes on the sale of their business, allowing them to fund greater philanthropic endeavors,” Kurz says.

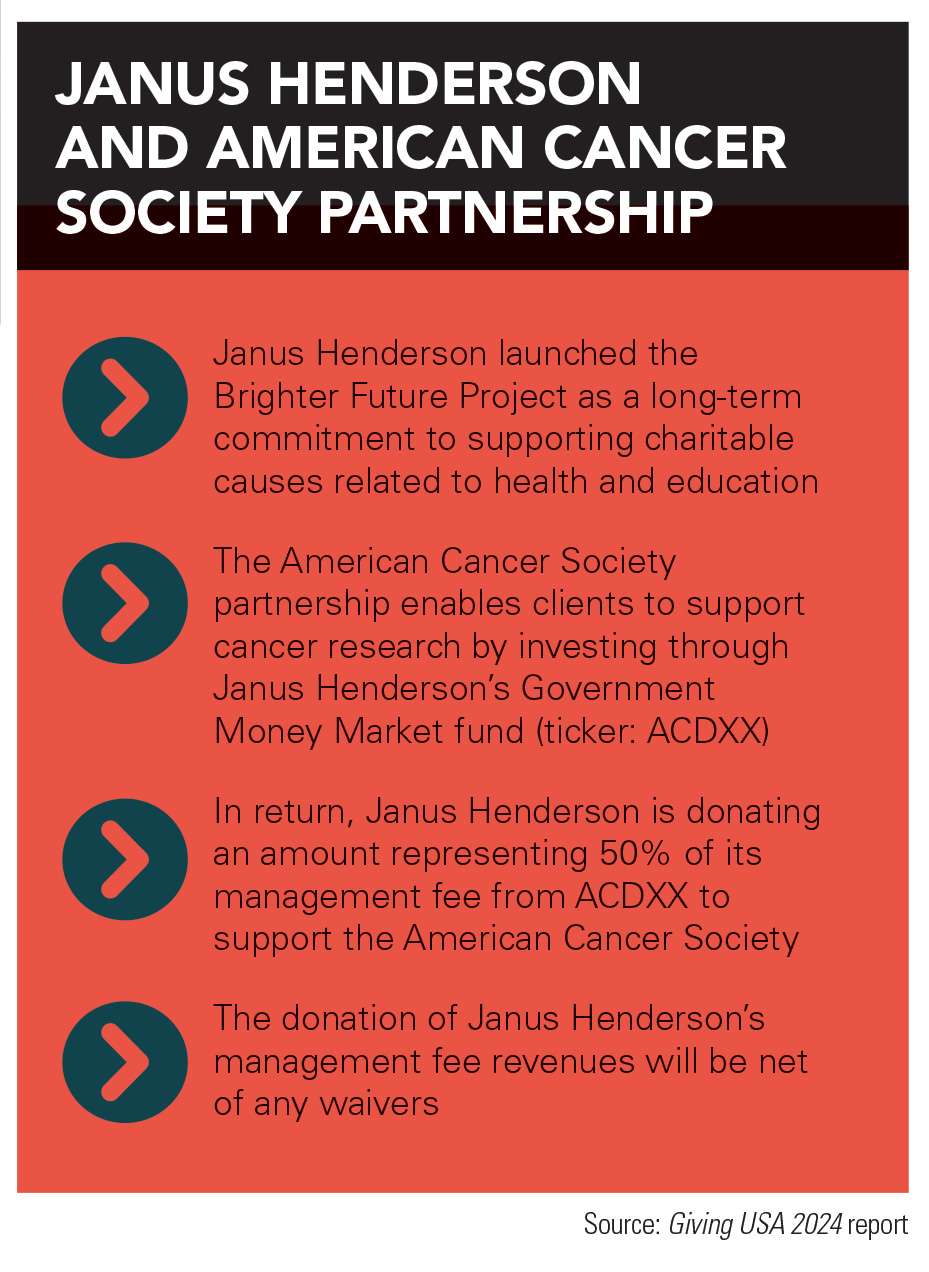

Finally, Nick Cherney, head of innovation at Janus Henderson Investors, offers a, well, innovative way for investors to give back. It’s called the Brighter Future Project, and it gives away 50 percent of the firm’s management fee from its government money market fund to support the American Cancer Society (ACS). The idea behind the program is to offer clients competitive yields on their cash at competitive fees and, in so doing, create long-term sustainable support for ACS, the leading organization in the world seeking to end cancer.

“It’s a pretty simple idea, really, but we are absolutely thrilled to be able to partner with clients and make it clear that our purpose as company, investing in a brighter future together, is about helping to deliver superior financial outcomes, but also about people leading long, healthy, and rewarding lives,” Cherney says.

The most common misstep seen among advisors is approaching charitable planning too late in the conversation, or using it only as a tax tool.

“When philanthropy is siloed from the broader wealth management process, advisors miss the chance to align it with estate planning, retirement income, personal values, and legacy goals,” Kurz says.

In Kurz’s view, advisors need to navigate a client’s or family’s “cognitive dissonance” when their actions don’t align with their values. When advisors lead these alignment conversations, clients tend to light up when philanthropy is framed as a core pillar of their financial planning strategies, according to Kurz.

“It deepens trust, opens intergenerational dialogue, and often leads to more sophisticated planning opportunities,” Kurz says.

Thomas Decker, wealth advisor (CPWA) at Cerity Partners, says a common mistake he often sees advisors make when integrating philanthropy into financial plans is assuming that a client should give − or wants to give − based purely on the financials. While charitable giving can provide potential tax and estate planning benefits, it should ultimately stem from personal values and internal motivations.

“Our approach is to first understand the ‘why’ behind a client’s interest in giving,” says Decker. “From there, we incorporate philanthropic strategies that align with their goals, then illustrate the financial advantages associated. By anchoring the conversation in the client’s original purpose for giving, we ensure that any giving strategy is not only efficient but meaningful.”

Decker added: “A donor-advised fund, private foundation, or even any charitable trust entity may serve as a meaningful forum to start imparting not only philanthropic family values with the next generation, but also for family financial and wealth management education.”

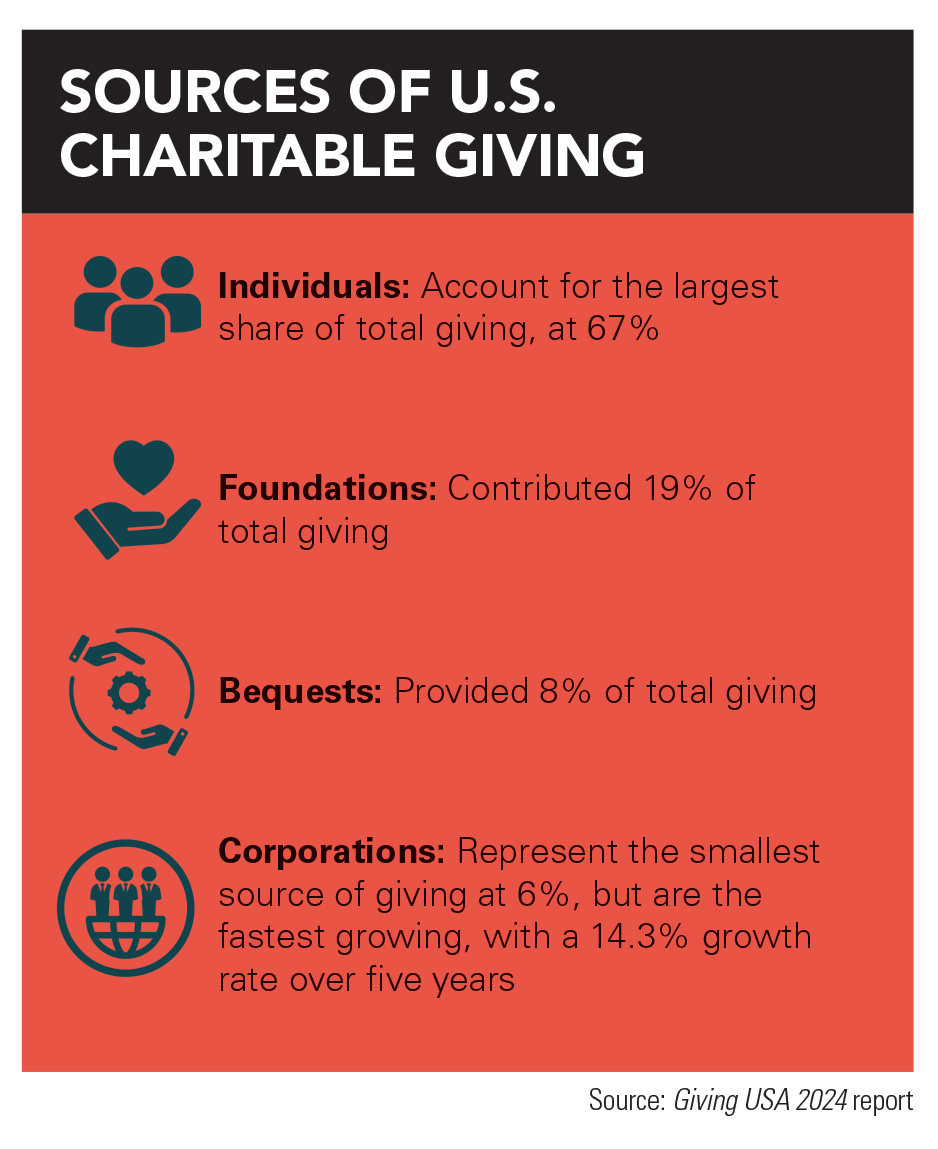

Household net worth has increased dramatically since the post-COVID decline in 2022, producing a more receptive donor base, according to PIMCO’s Nersesian. He points out that charitable giving in the US exceeds $500 billion annually, and donors often suggest their giving is motivated by a desire to give back to causes they have a personal connection with, as opposed to tax benefits or market conditions.

Advisors say if clients experience a bear market or see a significant pullback in stocks, the marketplace will anticipate a pivot in how clients give rather than if they give.

“More may lean on donor-advised funds or deferred-giving vehicles, preserving cash while still fulfilling charitable goals,” Kurz says. “Clients may reduce their annual contributions or need to ‘bunch’ or combine multiple years of planned contributions into one tax year to gain the tax advantage of possible charitable deductions.”

Cerity’s Decker, meanwhile, says he often looks for opportunities to pair charitable giving with other tax-efficient strategies, such as Roth conversions, in times of market pullbacks. For example, funding a donor-advised fund, CRT, or private foundation may help manage the potential tax impact of converting pre-tax assets to Roth, potentially creating a planning opportunity in a volatile environment.

Since Vis Raghavan took over the reins last year, several have jumped ship.

Chasing productivity is one thing, but when you're cutting corners, missing details, and making mistakes, it's time to take a step back.

It is not clear how many employees will be affected, but none of the private partnership's 20,000 financial advisors will see their jobs at risk.

The historic summer sitting saw a roughly two-thirds pass rate, with most CFP hopefuls falling in the under-40 age group.

"The greed and deception of this Ponzi scheme has resulted in the same way they have throughout history," said Daniel Brubaker, U.S. Postal Inspection Service inspector in charge.

Stan Gregor, Chairman & CEO of Summit Financial Holdings, explores how RIAs can meet growing demand for family office-style services among mass affluent clients through tax-first planning, technology, and collaboration—positioning firms for long-term success

Chris Vizzi, Co-Founder & Partner of South Coast Investment Advisors, LLC, shares how 2025 estate tax changes—$13.99M per person—offer more than tax savings. Learn how to pass on purpose, values, and vision to unite generations and give wealth lasting meaning