Craig Froelich’s a-ha moment occurred immediately after he presented to Bank of America colleagues about how the company intended to better include neurodiverse staffers.

“My inbox was full afterwards, there were so many people in the organization, whom I worked with every day, who fell into this category,” said Froelich, the bank’s chief information security officer. His surprise validated the effort he embarked on about three years ago to gradually retool communication, assignments and work conditions to suit the individual needs of those who think differently.

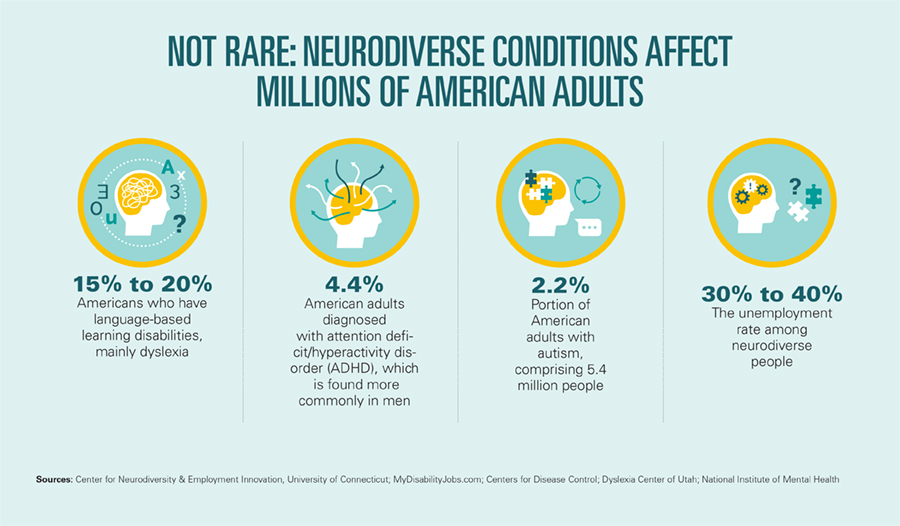

Employers are getting smarter about recruiting and working with neurodiverse individuals — those with autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, post-traumatic stress disorder and other conditions that affect cognitive processing but not intelligence, aptitude or attitude. While technology jobs are often assumed to be a good fit for neurodiverse people, advocates and employers in the investment sphere say the bigger lesson is that adapting for the neurodivergent community often makes the workplace better for all.

That’s what clued in Froelich to begin with. He was talking with a team member “and she said, ‘I’m neurodivergent and if you send me the meeting materials in advance, we can have a better conversation,’” he related. “I hadn’t ever heard that term, and who doesn’t want the materials in advance of the meeting?”

Neurodiversity is having a moment — there’s even an investment index. Recent clarifications in terminology have equipped employers with language to more confidently signal that they offer accepting cultures and career paths for people who historically have been hesitant to divulge their cognitive issues, instead quietly adapting on their own. The very definition of disability has generally centered around physical access and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, while neurodiverse conditions often are invisible to co-workers.

The neurodivergent sphere merges cognitive differences with diversity, in that people who think differently qualify for accommodations that primarily pivot around information processing, not the literal process of getting to work, seeing or hearing.

Clients who are neurodivergent, or who have neurodivergent family members, provide insight into hiring and managing neurodiverse talent, too, said Charlie Massimo, senior vice president at Wealth Enhancement Group, as they figure out career paths that build on neurodiverse strengths.

Froelich’s epiphany is typical of employers who are realizing that creating a workplace that welcomes neurodiverse employees is more about evolution than accommodation, said Marcus Soutra, president of Eye to Eye, a nonprofit that helps schools better integrate neurodivergent students, including career guidance. “It’s just another type of diversity. People want to be seen and valued, so that when they disclose, they are accepted and understood,” he said.

About 80% of young adults don’t disclose to their employers that they have learning differences, Soutra said. “That shows you that the culture comes first, and then systems and practices come after that.”

Workplace accommodation consultant Kerry Magro describes himself as an “extroverted autistic.” “Stereotypically, we’re good at math,” he said of people with autism. And, in fact, he is good at math — but just as good at developing training materials and speaking in front of groups.

Employers are catching on to the high return on investment for helping neurodivergent employees get their groove, Magro said, citing research that indicates neurodivergent employees “tend to stay on the job longer and the majority of their accommodations cost nothing.”

“Neurodivergent employees require managers to be flexible ... and adaptable.”

Theresa Haskins, CEO, Haskins Consulting Group

Some of the characteristics commonly shared by neurodiverse people — a longer adjustment period to workplace culture and communication, and a longer learning curve regarding the social elements of work — also make them loathe to leave a workplace where they are established and accepted, Magro said.

As Froelich discovered, practical steps are both easily adopted and often universally welcomed, Magro said. “A big one is how to receive instructions,” he said. Neurodiverse people often prefer written materials “so they can review it and go over it with a mentor or coach. Vague instructions are challenging and vague expectations are impossible.”

“Many of these techniques work well for everybody,” said Theresa Haskins, an associate professor at the University of Southern California and CEO of Haskins Consulting Group. When her son, now in college, was diagnosed with autism, she translated her experience in financial services to a new career researching ways that autistic people can build thriving careers and how employers can best integrate with them.

“Neurodivergent employees require managers to be flexible in their approaches and adaptable to change,” she said. “Think less about how something is done and more about what needs to be done, that’s how you open the door for neurodivergents — and for creativity and innovation, too.”

Some elements of neurodiversity, for some people, offer unexpected upsides, too, she said.

“In my research, all the managers said that autistic employees were easy to correct. When there’s a problem, you just tell them and they say, ‘OK.’ People with autism tend to be literal,” Haskins explained. Massimo agrees. “Many divergent individuals can focus solely on the task,” he said. “They are so attuned to getting a job done well, that their sense of accomplishment is much greater.”

Once the ice is broken, crafting supportive work conditions is usually a matter of adjusting lighting, noise and activity levels for optimum productivity, Magro and Haskins agreed.

And Froelich added that neurodiverse employees look for opportunities for growth and advancement just as much as anyone else. Converting a perceived drawback to a professional strength can even become part of someone’s personal platform, as demonstrated by Charles Schwab, who has dyslexia, and went on to build a huge personal finance and investment brand.

“If you lead with the idea that neurodiverse people have disabilities, you’re missing the point,” Froelich said. “More often than not, people with neurodiverse issues have a spectrum of abilities, and it’s a matter of matching what they’re good at with the work you have to get done.”

Eliseo Prisno, a former Merrill advisor, allegedly collected unapproved fees from Filipino clients by secretly accessing their accounts at two separate brokerages.

The Harford, Connecticut-based RIA is expanding into a new market in the mid-Atlantic region while crossing another billion-dollar milestone.

The Wall Street giant's global wealth head says affluent clients are shifting away from America amid growing fallout from President Donald Trump's hardline politics.

Chief economists, advisors, and chief investment officers share their reactions to the June US employment report.

"This shouldn’t be hard to ban, but neither party will do it. So offensive to the people they serve," RIA titan Peter Mallouk said in a post that referenced Nancy Pelosi's reported stock gains.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.