The otherwise innocuous boilerplate warning about past investment performance not necessarily being indicative of future returns has morphed into a bitter dispute surrounding a 36-year track record that's promoted by Equity Investment Corp.

The $4.1 billion Atlanta-based asset manager, known colloquially as EIC, which offers separate account strategies through tens of thousands of reps on most of the major brokerage platforms, is battling to tamp down claims by the firm’s founder, James Barksdale, that its publicized track record dating to 1986 is illegitimate.

The full narrative is detailed and convoluted but essentially boils down to a he-said, they-said situation, while also highlighting gaps in regulatory oversight when it comes to separate account performance histories.

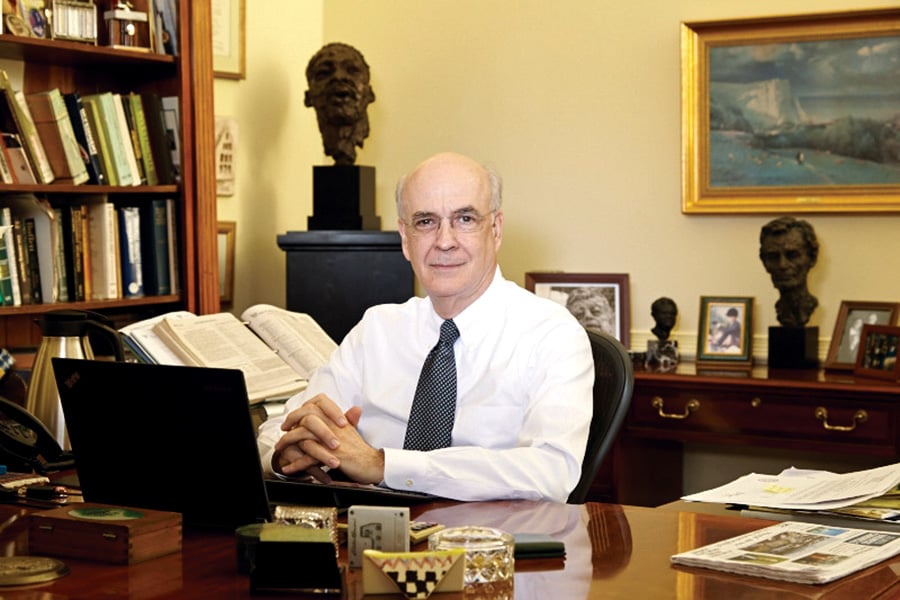

“It is an authentic track record from 1986, when I started the firm, to September 2016,” said Barksdale, 68, who describes himself as acting as a whistleblower against the current owners of the firm, which became EIC through an unorthodox ownership conversion.

The EIC leadership that Barksdale is at loggerheads with includes three people he hired over the years to help him manage portfolios: Andrew Bruner, 53, who was hired in 1999; Terry Irrgang, 64, who was hired in 2003; and Ian Zabor, 46, who was hired in 2005.

The situation, which has mutated beyond the track record dispute into a formal lawsuit by EIC against Barksdale, sheds light on how things can go sideways for independent asset managers running separate account portfolios.

As part of the ownership change, Barksdale transitioned from lead investment manager to serve as chairman of EIC from September 2016 to February 2017, when his title was changed to manager of socially responsible portfolios. He cites 2016 as one of many breaks in the track record because that’s when he stopped being involved in investment decisions for the EIC strategies he had been running since 1986.

Barksdale references multiple Securities and Exchange Commission no-action letters, which are codified by the SEC’s new marketing rule that went into effect May 2021, to back up his claim that under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, a track record cannot be carried forward following investment manager turnover, among other reasons.

Barksdale also claims the original investment strategy has been altered and now deviates from the value investing approach he applied up until 2016.

At issue is the portability of separate account track records through firm ownership changes, portfolio manager turnover and evolving investment strategies.

Barksdale said he first filed a complaint with the SEC about the validity of the track record in October 2017 after he was unable to get answers internally as to how using the track record complied with the Global Investment Performance Standards and the SEC's marketing rules.

“I was a financial beneficiary to this enterprise,” he said. “I felt I had to go to the SEC, otherwise I could be accused of being a participant.”

Meanwhile, according to the EIC lawsuit, Barksdale, through the Barksdale Investment & Research (BIR) firm he launched in 2019, has been violating his non-competition agreement by marketing a track record established when he was with EIC, which happens to be the same track record EIC is marketing.

EIC's lawsuit challenges Barksdale's use of the track record, stating that "BIR has not existed for 36 years, nor does it have the right to claim either the alpha or the 1986 year-end EIC commentary," which Barksdale linked to in a report earlier this year.

Barksdale said his new firm doesn’t violate the non-compete agreement because he's only publishing investment strategies and not managing money in a way that would require registration with the SEC.

While the SEC hasn't yet made public any official ruling in the matter, much of Barksdale’s argument is grounded in the distinctions between the Investment Advisers Act and the Investment Company Act of 1940, which covers registered products like mutual funds.

The nuance is underscored in an email to InvestmentNews from Andrew Gilman, public relations representative for EIC, which cited the portfolio manager turnover of the 59-year-old Fidelity Magellan Fund as an example of track record portability.

“By analogy, Peter Lynch has long ago left the Magellan Fund, but Fidelity still utilizes the founder’s track record,” Gilman wrote.

But according to securities attorney Richard Chen, who is not involved in this case, it's not helpful to compare the track record of a registered mutual fund to that of a separate account strategy that is covered under the Investment Advisers Act.

“At the very least, it sounds like there’s a problem here because Jim Barksdale is not involved in the performance of the track record going forward, and they shouldn’t present the performance prior to the time where he was involved,” Chen said.

Some of the brokerage platforms currently promoting the full 36-year track record of EIC separate accounts include Charles Schwab, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Raymond James, UBS and Wells Fargo, each of which either declined to comment or did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Quoting the SEC's rules for marketing track records, Chen said investment advisers are prohibited from displaying predecessor performance unless the following requirements are satisfied:

“There’s no 100% clarity here because you’re talking about a standard that has four levers to pull,” Chen explained. “And the sale of the business is a complicating factor.”

The lawsuit filed by EIC on Feb. 28 claims Barksdale is violating the non-competition, non-solicitation and non-disparagement terms of the sale and business transition that the suit claims paid Barksdale approximately $10 million since 2016.

EIC did not respond to a request for comment regarding the lawsuit that was filed while research for this story was underway.

For his part, Barksdale disputes that the non-compete charge related to his promoting the track record for his own business by claiming “the agreement contains a carve-out clause for any activity that does not trigger registration as an investment adviser.”

Regarding the non-solicitation restrictions, Barksdale claims they "only apply to activities that are competitive to a firm’s activities.”

The EIC lawsuit claims Barksdale disparaged the asset manager by accusing it of "fraudulent advertising."

The suit states that Barksdale "repeated the lie that Barksdale, and only Barksdale, was responsible for investment decisions and therefore the achievement of the track records."

For his part, Barksdale describes the non-disparagement as “mutual." In essence, while EIC claims Barksdale is taking too much credit for the investment performance, Barksdale claims he isn't getting enough credit.

“The problem is that EIC’s core narrative, necessitated by their inability to meet SEC portability standards except by misrepresenting my role at original EIC, was inherently disparaging from the start — that is, the narrative that I was not involved with portfolios, didn’t know what was in them, etc., like I was a completely irresponsible chief investment officer who was not paying attention to the portfolios,” Barksdale said.

Specifically, Barksdale claims the current owners communicated to employees that “my performance before adding the team members [starting in 1999] was not good.”

He also claims the current owners made “statements to platforms and advisers that I had not been involved with original EIC’s investment decisions for years because I wanted to retire to pursue other interests.”

Barksdale added that the current ownership team made statements that investment decisions made prior to the sale “were team-based, suggesting consensus was required, rather than requiring my review and sole approval.”

Barksdale also cites EIC’s year-end 2021 commentary, which gives Bruner credit for the strong performance from 2000 to 2002 period, and gives Ian Zabor credit for the strong results during the 2007 to 2009 period.

“In fact, I had been navigating original EIC away from the tech bubble for years and hired Andrew [Bruner] in anticipation of its imminent demise and had been steering EIC away from the credit bubble for years and hired Ian in part because of my concerns about it,” Barksdale said.

Barksdale admits that his efforts to prevent his former company from using the full 36-year track record are mostly based on pride and principle because he gains nothing by preventing the use of the track record.

“My main goal is that the track record that I accomplished not be used to deceive investors by contravention of SEC and [Global Investment Performance Standards] requirements,” Barksdale said. “And, of course, I would like investors to have a pathway to benefit from the approach as well, since I believe in it, and it has worked now for 36-plus years. That record can be marketed profitably, and I would like to see EIC and all the platforms do so and benefit clients and grow relationships, but only if it is done in compliance with SEC requirements.”

Meanwhile, for the owners of EIC that spun off in 2016, having to update the performance track records of three separate account strategies to go back just six years or to some point between 1999 and 2005, when the current investment team joined the company, could have a negative impact on marketing the strategies.

Aside from a very brief phone conversation with Bruner, during which he described Barksdale as “wrong” and “disgruntled,” all communications with the company for this story were conducted through a public relations firm and outside legal representatives, and conversations were entirely on background, which means they were not for attribution.

Responding to a request for on-the-record answers to specific questions, EIC’s PR representative, Andrew McGowan, emailed the following statement that's attributed to Bruner, identified on the company website as director of research and portfolio manager: “Based on SEC guidance, we, along with our regulatory consultants and legal counsel, are extremely confident that as a continuation of a single firm we own the track records and may advertise them from inception with appropriate disclosures. Our investment decisions have been team-based since 1999, and our investment philosophy and processes have remained consistent. We are very disappointed that Mr. Barksdale continues to spread his false claims and theories in blatant violation of his covenants and warranties. Mr. Barksdale’s misconduct has left EIC no choice but to file suit to address his baseless accusations and his bad faith breaches of his contractual obligations.”

EIC’s Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS) composite report discloses the evolution of the investment management team in detail, including investment performance during the various periods of portfolio manager changes.

GIPS, which was created in 1999 and revised by the CFA Institute in 2005 to create a single global standard for investment performance reporting, represents a set of voluntary standards used by investment managers.

Investment managers aren't required to follow GIPS guidelines but if they claim to adhere to them, the SEC requires full adherence, Chen said.

David Spaulding, a securities attorney who specializes in GIPS performance and performance certification, said that despite an appearance of oversight, the CFA Institute has never pursued enforcement related to claims of GIPS noncompliance.

“I think [the CFA Institute’s] position is to avoid such policing,” Spaulding said. “That said, if the CFA charter holder is found to have done something unethical, such as making a false claim, their charter can be pulled or other action taken. But that, I believe, would be the extent of it.”

A representative for the CFA Institute was not able to provide anyone to comment for this story.

Regarding the reference to “SEC guidance” in Bruner's statement, which was supported in a follow-up email from the PR firm stating "the SEC has looked into the issue and has told them that utilizing the track record from its inception is a non-issue,” EIC did not provide any proof of that SEC guidance.

The SEC declined to comment for this story.

To better appreciate Barksdale’s passion for revising the investment performance data being used by EIC, it’s important to recognize that he describes his departure from the firm he founded as the result of a “coup” that unfolded while he was otherwise distracted.

It was March 2016 and Barksdale decided to run as a Democrat for Georgia’s open U.S. Senate seat — an idea Barksdale said was supported by his colleagues at EIC. (Barksdale lost in November to his Republican opponent, Johnny Isakson.)

In May 2016, two months after EIC announced Barksdale's Senate run, noting that he would continue his investment duties during the campaign, Bruner, Zabor and Irrgang incorporated a business named BZI Partners, which was renamed Five Falls Capital a month later.

On June 24, 2016, the trio submitted their letters of resignation, citing differences over investment decision making, despite the fact they did not have authority to make investment decisions independently, according to Barksdale.

After a few months of negotiations, it was decided that Barksdale would sell the EIC name and office assets to a new entity known as EIC Acquisition Co., created by Bruner, Zabor and Irrgang.

Barksdale said his compensation for the sale was a portion of the company revenues for the next three years while he acted as chairman initially until his title changed to manager of SRI portfolios six months later.

“They basically kicked him out," said Joyce Michels, who joined EIC in 1989 and was the chief compliance officer from 2004 through her resignation in April 2017.

“For whatever reason, Jim got involved in politics," she added. "I thought it was stupid, but he didn’t ask me. But at that same time, his mother was dying, and he was going through a divorce.”

Michels recalls the pressure on Barksdale from Bruner, Zabor and Irrgang to sell the business to them.

“They said we’re leaving unless you sell the business to us,” she said. “Jim’s big concern was if he let them go, he would lose a lot of business, so he finally went through with it.”

Both Michels and Barksdale insist a big part of the motivation for creating a separate company to acquire the original EIC was to get rid of the employee stock ownership plan, which divided ownership of the business among the employees.

EIC representatives didn't respond to multiple requests for a response to whether the ESOP played a role in the ownership transition strategy.

Beyond the sale of the EIC name and assets that included records and office equipment, the transfer of client assets under management was accomplished through assignment request letters sent out to each client, which represents another break in the investment management chain, according to Barksdale’s attorney, Jim Hermance.

“The SEC has rules that deal with advertising, but those rules are very vague in what they say,” he said. “So as long as you don’t commit fraud, most of the rules don’t say what you can and can’t do in advertising, but there are no-action letters related to this.”

Hermance, who previously worked in the SEC’s division of corporation finance, found several relevant no-action letters, but one in particular stood out as an example of the SEC’s rigidity with regard to the portability of track records.

An August 1991 no-action letter from the SEC prohibited Great Lakes Advisors from using a track record from a 1990 acquisition of Continental Capital Management Corp., even though the primary investment manager was still managing the portfolio.

According to the SEC’s letter, because the entire investment team from Continental Capital didn’t make the transition to the new company, using performance data from the period before the transition “would be misleading.”

“There are a number of considerations that the SEC says you must consider, and one is that the accounts that were managed have to continue to be managed substantially in a similar manner, and have to be managed by the same people,” Hermance said. “Jim went to the three guys, and they said based on their lawyer’s advice that they can continue to use the track record.”

But even if the Great Lakes situation appears similar to what happened at EIC, Hermance explained that the SEC’s no-action letters are not to be considered as precedent.

“No-action letters are not binding except for the circumstances of the no-action letter,” he said. “It is designed to tell advisers what the SEC’s interpretation of the rules are.”

At this point, Barksdale views the EIC lawsuit as a potential conclusion.

He said he'll accept whatever the court decides, but he won't stop investing and touting the track record he developed.

“I’ve been investing this way since I was 24 years old, and I don’t have any plans to stop,” Barksdale said. “I’ll accept the determination of the court if it’s decided they have the right to use the full 36-year track record. And I think a court will ultimately reach some conclusion that will encourage the SEC to take some action, or not take action. Even if the court rules in their favor, it doesn’t mean I can’t exercise free speech and say I was the sole portfolio manager from 1986 to 2016.”

Rajesh Markan earlier this year pleaded guilty to one count of criminal fraud related to his sale of fake investments to 10 clients totaling $2.9 million.

From building trust to steering through emotions and responding to client challenges, new advisors need human skills to shape the future of the advice industry.

"The outcome is correct, but it's disappointing that FINRA had ample opportunity to investigate the merits of clients' allegations in these claims, including the testimony in the three investor arbitrations with hearings," Jeff Erez, a plaintiff's attorney representing a large portion of the Stifel clients, said.

Chair also praised the passage of stablecoin legislation this week.

Maridea Wealth Management's deal in Chicago, Illinois is its first after securing a strategic investment in April.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.