Five years ago, three firms with some of the most prominent financial advisers in the advice industry — Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and UBS Financial Services Inc. — decided to rein in their mass recruiting of financial advisers working at competing firms.

It was a high-cost, high-risk business strategy that many senior wealth management executives on Wall Street regarded as a wash; the expense of recruiting was comparable to a sort of benign, necessary evil to compete as a wirehouse.

Instead, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and UBS decided to drive their advisers to grab more client assets. The firms focused on improving adviser technology, bettering financial planning to include banking and lending, and incentivizing their current hordes of thousands of financial advisers to bring in new clients and a bigger share of clients’ assets.

Fast forward to the end of 2021, and wealth management businesses across Wall Street were awash in record revenues and profits. The switch in strategy from half a decade ago has clearly worked for those three firms, although many advisers remain unhappy about upsetting the old system. A cutback in recruiting potentially meant a smaller marketplace for their services.

At Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and UBS, building a network of thousands of financial advisers is no longer just about increasing head count — now the true sweet spot for those firms, as measured by total head count and annual revenue per adviser, is boosting revenue per adviser and adding net new assets each quarter.

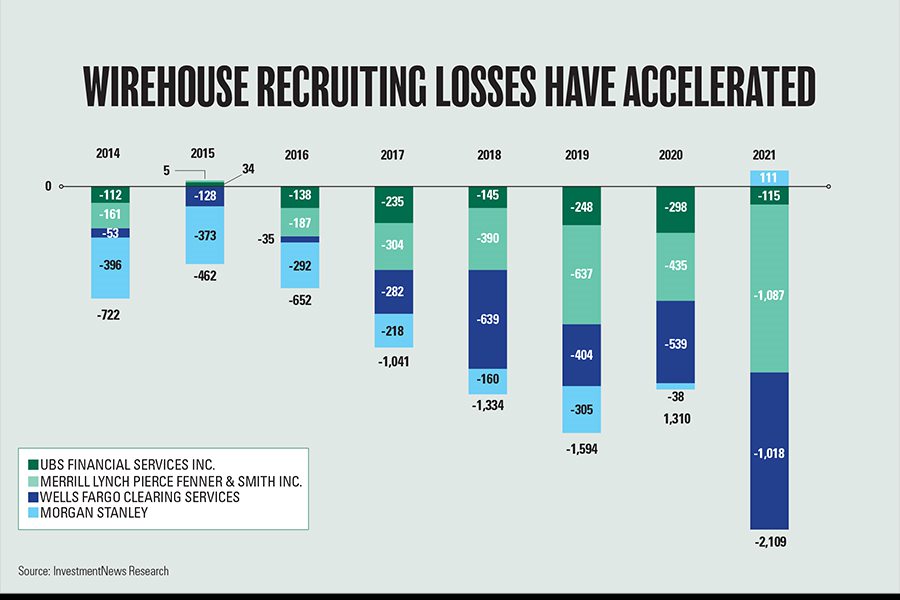

How far wirehouses have distanced themselves from boasting about recruiting and adding masses of advisers is shown quite starkly in their reporting to the public each quarter.

Last spring, Morgan Stanley stopped releasing its number of advisers, a clear break from industry norms, leaving the market to guess how many actually work there. Merrill Lynch Wealth Management now mushes together all the licensed people under its roof, as if to signal that a bank broker at Bank of America is no different than a wealth manager at Merrill Lynch or a call center adviser at Merrill Edge. At UBS, the number of financial advisers is buried in statistical disclosures each quarter, most recently on page 16 of 104.

By contrast, LPL Financial, the largest independent broker-dealer with more than 20,000 registered investment advisers and brokers, is in the business of recruiting and slaps its financial adviser head count on the front page of its quarterly reports.

In January, Morgan Stanley Chairman and CEO James Gorman was asked by an analyst during an earnings conference call to describe what was driving the firm’s terrific organic growth. How much came from retaining financial advisers versus recruiting them?

Morgan Stanley, Gorman noted, has simply put its reliance on recruiting in the rearview mirror. At the wirehouses, recruiting hinged on paying large bonuses, typically two to three times an adviser’s annual revenue, to experienced financial advisers. They then worked the bonuses off over time, usually over seven or nine-year periods.

“It’s not a simple answer because in the old days, it was simple,” Gorman said. “It was a function of money that you lost by financial advisers leaving and money you gain by recruiting financial advisers.”

“And obviously, that’s a sort of sorry way to run a business,” he said. “It basically settles your P&L for the next nine years to buy a little bit of joy in the near term. Fortunately, we’ve outgrown that.”

If the big firms don’t need to recruit financial advisers, what’s the next step to attract, develop and retain top financial adviser talent?

Ten years ago, the hiring of financial advisers at the wirehouses had a hammer and tongs feel and methodology; big bonuses got big advisers, and lots of them. Today, hiring advisers, training them and hanging on to them, as well as selectively recruiting them, are much more nuanced endeavors.

For example, after hunkering down on hiring advisers during the pandemic, Merrill Lynch is once again looking to bolster the size of its thundering herd. This year, it’s targeting more young financial advisers with limited experience in the industry and, more selectively, experienced advisers outside major metropolitan markets. UBS has been focused on hiring private bankers.

Acquisitions, a moribund market after the chaos of the credit crisis, are once again in vogue as an engine for growth. Morgan Stanley recently bought ETrade and Eaton Vance, while UBS this year said it was acquiring robo-adviser Wealthfront Corp.

“Head count is not a benchmark for success anymore.”

Dennis Gallant, senior analyst, Aite-Novarica Group

Merrill Lynch has crafted a strategy of hiring advisers that has four entry points, with recruiting experienced financial advisers merely one of those.

The plan ranges from hiring college graduates with no experience who become trainees to selectively recruiting experienced financial advisers in markets that the firm is looking to for greater reach, Andy Sieg, president of Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, said in a recent interview on the InvestmentNews Podcast.

“It’s a diversified approach to building our adviser team in the years ahead,” Sieg said.

“Big firms used to hire advisers so they would just have the numbers, and raise and lower head count for quarterly or annual reports and meetings,” said Dennis Gallant, senior analyst at Aite-Novarica Group. “Those metrics have clearly changed.”

“Head count is not a benchmark for success anymore at those three wirehouses,” he said. “It’s still key for independent broker-dealers but it’s far less important at the wirehouse firms. They’re not talking about it anymore, even though they frequently get asked about it during the earnings calls.”

“The big firms spent the past decade cutting the low-producing financial advisers and now want a next generation of home-grown financial advisers that will be tied to the bank,” Gallant said. “They don’t want to deal with the headache of the adviser threatening to jump to a breakaway or independent firm if he’s not treated the way he thinks he should.”

Tired of having to pay six-figure bonuses to replace some of their most productive brokers who left for competitors after the financial crisis, Morgan Stanley and UBS upended the wealth management industry near the end of 2017 by withdrawing from an agreement known as the protocol for broker recruiting, which makes it easier for financial advisers to leave one firm to join another. The agreement had been established in 2004.

The move, first by Morgan Stanley and then by UBS, was a determined effort to hold on to more of their financial advisers.

Under the protocol, firms agree that they will not enforce restrictive covenants, such as noncompete and non-solicitation provisions, in employment contracts as long as the departing brokers limit the client information they take with them to their new employer and agree not to contact their clients until after they leave. They may leave with a client’s name, address, phone number, email address and account title.

Merrill Lynch remained in the agreement, but cut back on recruiting nonetheless, pursuing a multipronged strategy to grow its business, including creating a new pay plan deemed the “growth grid” that goosed its advisers to chase more new households.

The fourth and last-standing wirehouse firm, Wells Fargo Advisors, also remains in the protocol and has continued to recruit financial advisers by paying bonuses. But it has traveled a rocky road since 2017, when the scandals emanating from its parent, Wells Fargo & Co., began to spill over to Wells Fargo Advisors, which has seen a decline of thousands of advisers over that time, some from displeasure with the bank, some from retirement.

Tearing up the broker protocol didn’t occur in a vacuum. Indeed, it was part of concentrated strategies at both Morgan Stanley and UBS to keep brokers and advisers tied to the firms, industry executives said. That kicked off in the spring of 2016, when UBS said it was pulling back from recruiting to focus more on services and technology for its current workforce.

For Morgan Stanley, UBS and Merrill Lynch, the move away from recruiting, once regarded as the lifeblood of a brokerage firm, appears to have paid off. The S&P 500 repeatedly hit record highs during 2021, benefitting brokerage firms and banks immensely.

In 2021, Morgan Stanley and its close to 16,000 financial advisers brought in record net new assets for the year of $437.8 billion, for an annual growth rate of 11%, according to the company. During a conference call in January with analysts, Gorman called that rate of growth “freakish.”

UBS global wealth management Americas, with 6,218 advisers at the end of last year, delivered a pretax profit of $2 billion for 2021, which was a record and marked a 47% increase year over year, according to the company. The performance was supported by an 18% increase year over year in revenue per adviser and record loan volume of $92 billion, according to the company.

And Merrill Lynch posted record revenue of $17.4 billion in 2021, a 14% year-over-year increase. Client balances reached a record $3.2 trillion by the end of December, another 14% annual increase. The word “record” was used 25 times in a summary released to reporters in January of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch’s 2021 wealth management highlights for last year. Bank of America/Merrill Lynch reported 18,846 advisers at the end of last year, including Merrill, Bank of America private bank and consumer investments.

”When Morgan Stanley withdrew from the broker protocol in 2017, a big part of the firm’s reasoning was to get branch managers focused on advisers using new technology rather than chasing potential recruits at breakfast or lunch,” said Jed Finn, chief operating officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management.

“When you’re rolling out billions of dollars of technology for the advisers and trying to get them to adapt, you need leadership and branch managers to be around and focused on it,” Finn said. “Recruiting is one tool in the kit. We’re now seeing a massive flow of leads in the self-directed business, for example,” he added, referring to investors at the recently acquired ETrade who may want to work with a financial adviser in the future.

The days of recruiting reigning supreme at the wirehouses are long gone.

“It’s more true than ever — at the wirehouses, it’s all about locking in the current clients and adviser teams and practices,” said Danny Sarch, a veteran industry recruiter. Pushing lending products and alternative investments that are unique to that firm are part of the strategy.

“They want clients to be stickier to the firm,” Sarch said. “The strategy is, tie the customer to the firm so there is loyalty to the institution rather than the individual adviser.”

A Texas-based bank selects Raymond James for a $605 million program, while an OSJ with Osaic lures a storied institution in Ohio from LPL.

The Treasury Secretary's suggestion that Trump Savings Accounts could be used as a "backdoor" drew sharp criticisms from AARP and Democratic lawmakers.

Changes in legislation or additional laws historically have created opportunities for the alternative investment marketplace to expand.

Wealth managers highlight strategies for clients trying to retire before 65 without running out of money.

Shares of the online brokerage jumped as it reported a surge in trading, counting crypto transactions, though analysts remained largely unmoved.

Orion's Tom Wilson on delivering coordinated, high-touch service in a world where returns alone no longer set you apart.

Barely a decade old, registered index-linked annuities have quickly surged in popularity, thanks to their unique blend of protection and growth potential—an appealing option for investors looking to chart a steadier course through today's choppy market waters, says Myles Lambert, Brighthouse Financial.