Passive ETFs are not the answer to emerging markets investing

One problem: Indexes used by most investors have big concentrations in countries that are not emerging anymore.

When considering investments in emerging markets, many investors turn to passive exchange-traded fund strategies due to the common perception they offer a low-risk, inexpensive exposure to the equity markets of the developing world.

Passive ETFs are typically based on market capitalization indexes, with two popular solutions being Vanguard’s FTSE Emerging Markets ETF (VWO) and iShares’ MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM). Historically these two funds account for a large portion of the inflows to emerging markets equities. Due to recent strong relative performance and favorable valuations, both are currently experiencing strong inflows, with VWO and EEM seeing a combined $4.1 billion of inflows quarter-to-date, as of Aug. 31.

PASSIVE ETFS HAVE CONCENTRATION RISK

However, there are some fundamental problems with the construction of these ETFs, primarily based on the methods used to build the underlying indexes. While it is hard to argue that market capitalization is not an appropriate way to construct the investible universe of emerging markets equities, this weighting scheme impedes an investor hoping to get a reasonable exposure to the emerging markets in two ways.

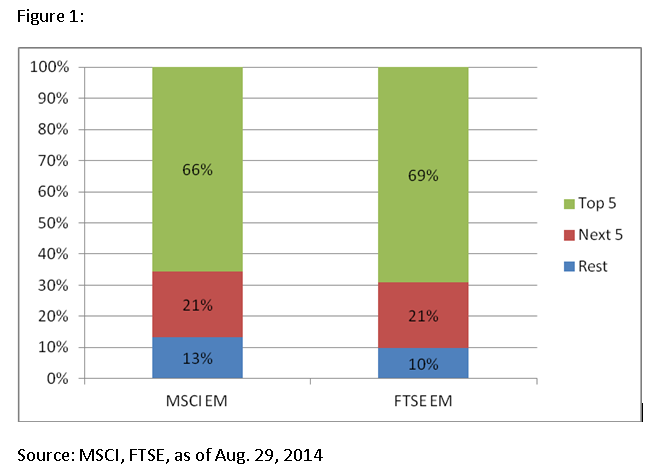

First, both the MSCI and FTSE Emerging Markets indexes are quite concentrated. In both indexes, China represents close to one-fifth of the underlying portfolio, and the top five countries represent over 65% of the exposure (Figure 1).

Stated plainly, a concentrated portfolio is risky because the concentrated positions drive the portfolio’s performance and the benefits of diversification are greatly reduced. This is particularly true in emerging markets, where the high volatility of country returns, paired with a low level of correlation among countries, means the foregone diversification benefit can be material. It is our experience that simply diversifying country exposures can add dramatic value versus the more concentrated benchmarks, in the form of both higher returns and lower volatility. By investing in the more concentrated portfolios represented by VWO and EEM, uninformed investors are most likely taking on a degree of unintended portfolio risk, which leads to lower expected returns than a portfolio constructed to have a more diversified set of country weights.

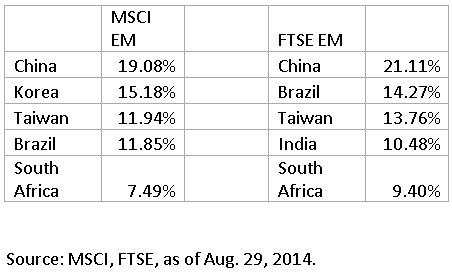

The second troubling aspect of these passive ETFs is the nature of the countries in which they are concentrated. For many investors, an investment in the emerging markets is an attempt to capture the larger growth potential of the immature economies of the world. In addition, many also invest in order to gain exposure to equity markets that are less knit into the global economy, and that have shown lower correlation with developed market equity returns. However, when looking at what countries make up the concentrations in VWO and EEM, we see a number of countries that are arguably on the verge of becoming developed. This means these countries are much further along their economic growth path than the smaller, less mature emerging economies. This results in expected growth rates much closer to the developed world than their less developed, emerging peers. In addition, these larger emerging countries are also more tied to the global economy, with equity returns more correlated with those of the developed world. The top five countries in either index show examples of such “mature” emerging economies:

China, after seeing explosive growth in its economy over the last decade, has in recent years seen its GDP growth rate converge toward that of the developed world. The inclusion of Korea and Taiwan as emerging market countries surprise many investors, as both are perceived to be almost completely developed and, in fact, the FTSE Index has already graduated Korea to developed status. Similar statements can be made for Brazil and South Africa. For many investors hoping to lock in the higher growth rates and correlation benefit of emerging economies, the large weights assigned to these countries acts against this investment thesis.

A BETTER WAY

In our experience, a more diversified emerging markets portfolio — one with underweights to the notable concentrations shown above, and an overweight to those smaller economies that more closely deserve the “developing” title — solves these risks on both fronts. This approach harnesses the power of diversification to provide a portfolio with a higher expected return and lower expected volatility. It also more closely matches investor motivation for investing in the emerging markets by underweighting countries that are arguably developed or near-developed, and overweighting those countries that truly are in their infancy and still have some of their hyper-growth days ahead of them. For investors looking for less risk than in the index-based ETFs we have examined above, we note a variety of more broadly diversified solutions in the marketplace.

Tim Atwill is managing director, investment strategy, at Parametric.

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.