MF Global meltdown shows the wisdom of prop-trading limits

MF Global took large bets on commodities, government debt, futures and derivatives, and did so with its own capital. Companies that risk their own money, or that of wealthy clients, should be allowed to fail.

The bankruptcy of MF Global Holdings Ltd. is the first major U.S. casualty of the European sovereign- debt crisis. The trading firm’s demise is no small matter: Its $40 billion in debt is on the scale of Chrysler’s 2009 failure.

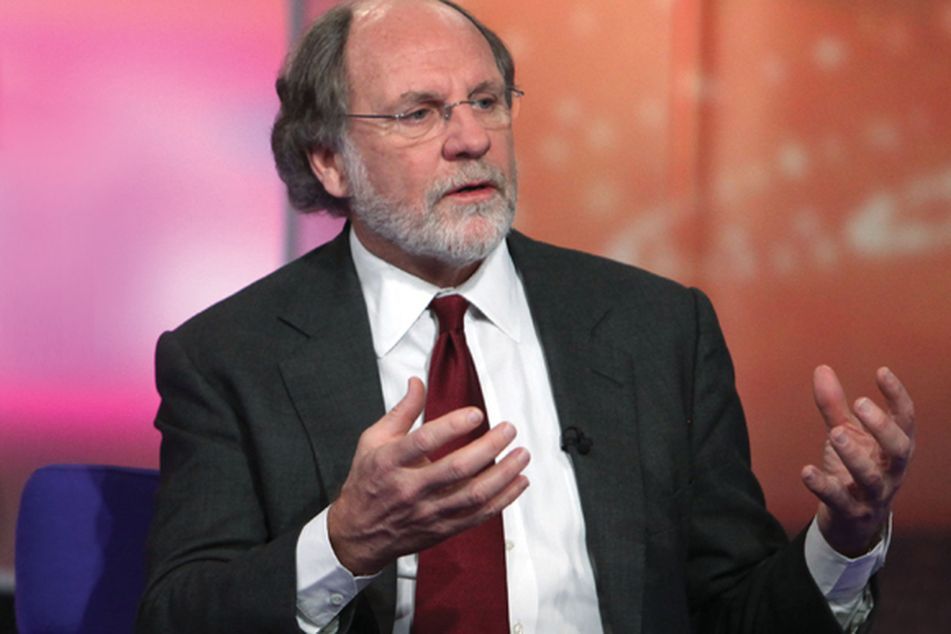

The MF meltdown is also sad news for creditors, shareholders and almost 3,000 employees, not to mention a humbling blow to Chief Executive Officer Jon S. Corzine, the former Goldman Sachs head, U.S. senator and New Jersey governor.

So is there anything to be learned from this mini- cataclysm? Well, yes. Three things, actually.

Lesson No. 1 is that there is no need for — indeed, no one is even suggesting — a bailout. MF Global took large bets on commodities, government debt, futures and derivatives, and did so with its own capital. No federally insured bank deposits or Federal Reserve discount-window loans were involved. Companies that risk their own money, or that of wealthy clients, should be allowed to fail.

Almost as soon as he arrived in 2010, Corzine set out to make MF Global a junior version of Goldman Sachs by diversifying his new firm, which until then had mostly arranged and processed trades for banks, corporations and other investors. MF Global, formerly part of Man Group Plc, was founded as a sugar broker by James Man in England in 1793. It was spun off as a public company in 2007.

The financial crisis and economic decline put a dent in trading revenue as investors reduced their risk appetites and generally had less money for trading. So Corzine pumped up the firm’s proprietary trading desk, using its small base of capital to buy European sovereign debt.

Poor Timing

To say the least, Corzine’s timing was poor, coming as many Wall Street firms were spinning off or shrinking proprietary trading desks and reducing their risk. MF Global went in the opposite direction by buying the debt of Italy, Spain, Belgium, Portugal and Ireland, ignoring warnings of default by one or more of those countries.

The company now holds more than $6 billion in euro-area debt, the value of which has since tumbled. It also tried to earn interest off those assets in the overnight repurchase market. To do all this, the firm borrowed $40 for every $1 in capital, according to Egan Jones, a rating service. That’s more leverage than Lehman Brothers Holdings had when it collapsed in 2008.

And that raises lesson No. 2: Regulators this time didn’t wait for disaster to befall MF Global and its trading partners. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, the overseer of trading firms like MF Global, in September required it to reduce its leverage by setting aside more capital.

The unraveling came quickly. The short-term cash lenders that MF Global depended on began demanding more collateral for their loans. Ratings companies downgraded the firm, with Moody’s Investors Service citing the firm’s “outsized proprietary position.” The firm on Oct. 25 reported a net loss of almost $192 million for the latest quarter, the ninth loss in the past 11 quarters. Once Bloomberg News reported on Oct. 28 that MF Global had tapped out two of its credit lines, the shares plummeted and the firm was, for all intents, dead.

Because none of these activities took place within a bank, MF Global’s failure is contained within a relatively small circle of owners, lenders, counterparties and customers. This isn’t to minimize the large and painful losses, but there are no public losses and, so far, little systemic fallout.

And therein lies lesson No. 3: MF Global’s wagering is a reminder why the Dodd-Frank financial reform law bars banks from making high-risk bets with depositors’ money. As Bloomberg View has written before, a big gamble that goes wrong can deplete the capital a commercial bank needs to fulfill its basic lending function. It can also put taxpayers on the hook for a bailout.

The Volcker rule, named after Paul Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chairman, would curb banks’ ability to make speculative bets for their own profit. The details of the rule are up for grabs, and will be the subject of future editorials. There’s nothing wrong with proprietary trading — it just shouldn’t be done by federally insured, deposit-taking banks, a lesson MF Global’s collapse amply demonstrates.

–Bloomberg News–

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.