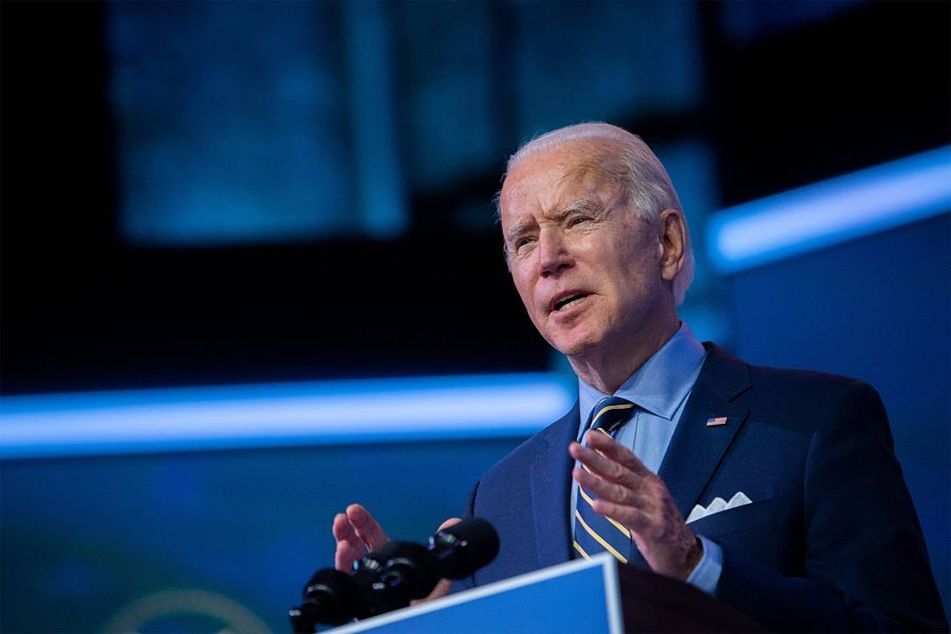

How Biden’s billionaire tax would hit the wealthy

Under Biden's plan, wealthy individuals would owe taxes on the unrealized gains of their assets, in addition to realized gains, a change that would upend long-standing tax principles.

President Joe Biden’s proposal for a “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax” raised a number of questions among America’s ultra-rich and those advising them.

Chief among their concerns: How would it work in practice, and what are the chances it actually becomes law?

The plan, which would tax the appreciation of financial and business assets owned by people worth more than $100 million, has strong support among many Democratic voters. It could generate hundreds of billions of dollars in new revenue from a group that has traditionally used tax laws to lower their Internal Revenue Service payments.

It’s a new iteration of an old idea. A decade ago, President Barack Obama pitched the so-called Buffett Rule, named after Warren Buffett, after the billionaire said the law allows him to pay a lower tax rate than his secretary.

Biden’s proposal would only affect a sliver of Americans. Still, it’s unlikely to be passed anytime soon in Congress, where Democrats have razor-thin margins, because many moderate lawmakers are skittish about such a big tax overhaul.

Here are answers to some of the most-pressing questions on Biden’s billionaires tax.

HOW WOULD THE TAX WORK?

The proposal would require that taxpayers worth more than $100 million pay a minimum of 20% on their capital gains each year, regardless of whether they sold assets for a profit or continue to hold them.

Currently, taxes are only owed when a gain is “realized” — in other words, after selling a stock or a stake in a company. Under Biden’s plan, wealthy individuals would owe taxes on the unrealized gains of their assets as well, a change that would upend long-standing tax principles.

The proposal would require taxpayers to track and report their overall wealth and gains to the IRS each year. It would let the tax payments on unrealized gains be spread out over several years. People with illiquid holdings, like a business or real estate, wouldn’t have to pay the full tax on the gain until they sell, but they would owe a deferral charge each year.

HOW MANY PEOPLE WOULD PAY THIS TAX?

The $100 million wealth threshold means the richest 0.01% of Americans — roughly 20,000 households — would owe this tax.

The White House estimates it would generate about $360 billion in revenue over a decade, with more than half of that coming from households worth more than $1 billion.

HOW DO THE WEALTHY AVOID TAXES NOW?

The IRS code currently only taxes income, not the gain in a stock portfolio or overall wealth, and many of the richest Americans have little income each year relative to their overall fortunes.

Mega-millionaires and billionaires have the flexibility to choose when they sell their holdings and can offset taxable gains with losses, deductions or other benefits. Many don’t have to sell often — or at all — because they can borrow against their wealth when they need to access cash instead.

That means that the richest Americans can frequently defer IRS liabilities for many years, and sometimes indefinitely.

WHY IS THIS IDEA GAINING POPULARITY?

Proponents for taxing unrealized gains say that the current tax code has one set of rules for most Americans, who are taxed regularly through paycheck withholding, and another for the wealthiest, who can choose when or if they pay.

A White House report last year found that billionaires on average pay an 8.2% tax rate, far lower than the middle class. Democrats who support this idea argue that it’s a way to fund new investments in the climate, childcare and health care sectors. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden has been working on proposals similar to Biden’s and acting as an advocate for the idea.

WHAT’S THE ARGUMENT AGAINST THIS PLAN?

Opponents say this would upend long-standing rules that only tax income once it’s realized. Republicans and some Democrats say it’s unfair to tax so-called phantom income, or gains on paper where there isn’t any cash.

Tax professionals say this would be an administrative nightmare for both the IRS and those who have to pay the tax, and would lead to lots of fights over the worth of hard-to-value assets. Legal scholars have also questioned if it’s constitutional.

HOW DOES THIS COMPARE TO A WEALTH TAX?

Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders both ran on the idea of a wealth tax during the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries.

That goes one step beyond Biden’s latest plan and would not only tax unrealized gains, but put an annual levy on the entire accumulated wealth of the richest Americans.

Biden rejected an outright wealth tax during the campaign, but the ethos of taxing billionaires has become a key policy priority for Democrats since then.

WHAT ARE THE POLITICAL PROSPECTS FOR A BILLIONAIRES TAX?

In the short run, not great.

Within hours of Biden’s proposal being released, Sen. Joe Manchin, a Democrat who is often a swing vote in the chamber, rejected the idea, calling it a “tough one.” He said he preferred other ways of taxing the very wealthy.

Longer term, the idea of taxing unrealized gains is likely to become a common talking point in Democratic politics. The concept has gone from a fringe idea popular only among very progressive lawmakers to a mainstream Democratic policy in only a few years.

[More: Advisers place little faith in Biden’s ‘billionaire tax’]

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.